Every year, thousands of older adults end up in the hospital not because of a fall or infection, but because of a medication they were told was safe. For people over 65, taking multiple prescriptions is common-some take five, ten, even more. But not all of those pills are right for them. That’s where the Beers Criteria comes in. It’s not a law, not a ban, but a clear, evidence-based guide that tells doctors and pharmacists which medications carry more risk than benefit for seniors.

What Is the Beers Criteria?

The Beers Criteria is a list of medications that healthcare providers should avoid or use with extreme caution in adults aged 65 and older. It was first created in 1991 by Dr. Mark Beers, a geriatrician who noticed how often nursing home residents were given drugs that made them more confused, dizzy, or constipated. In 2011, the American Geriatrics Society (AGS) took over the list and began updating it every three years. The latest version came out in May 2023, after reviewing over 7,000 studies.This isn’t just a list of bad drugs. It’s a practical tool designed to reduce harm. Older adults make up just 13.5% of the U.S. population but take 34% of all prescription medications. That’s a lot of pills-and a lot of chances for something to go wrong. About 23% of seniors living at home are taking at least one medication flagged by the Beers Criteria. And those medications are linked to 15% of hospital stays in this age group.

Five Ways the Beers Criteria Works

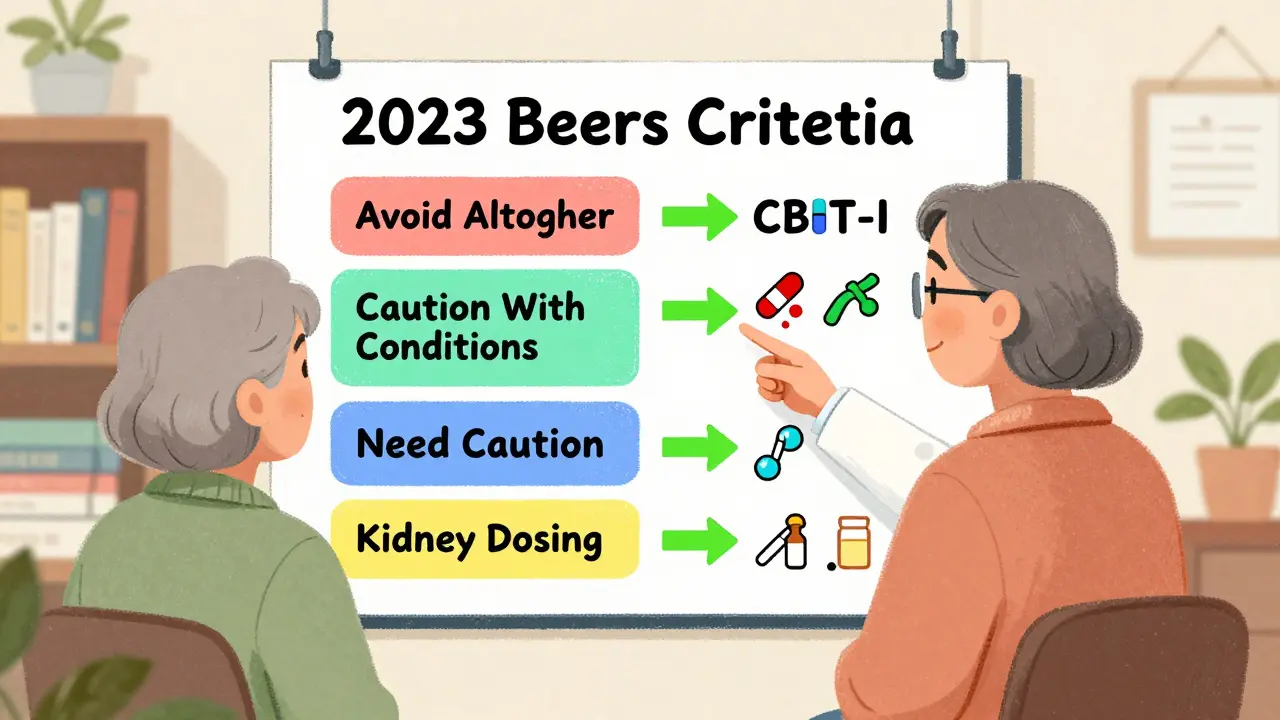

The 2023 update organizes the list into five clear sections, making it easier for doctors to use in real time.1. Medications to Avoid Altogether

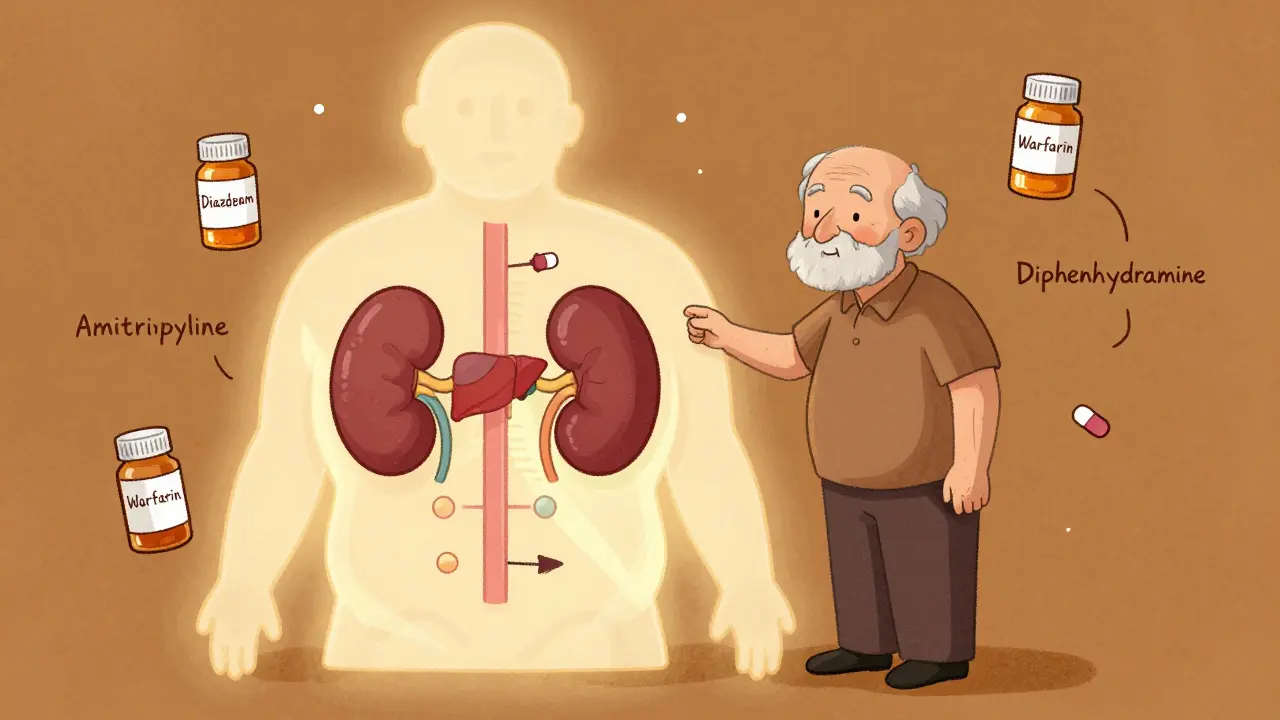

Some drugs are simply too risky for older adults. First-generation antihistamines like diphenhydramine (Benadryl) and hydroxyzine are on this list. They’re often sold over the counter as sleep aids or allergy meds. But they block a brain chemical called acetylcholine, which can cause confusion, memory problems, dry mouth, and constipation. In seniors, these side effects aren’t just annoying-they can lead to falls, delirium, or even permanent cognitive decline.

2. Medications to Avoid With Certain Conditions

A drug that’s fine for one person might be dangerous for another. For example, NSAIDs like ibuprofen and naproxen are common pain relievers. But if someone has heart failure, these drugs can cause fluid retention and make the heart work harder. The Beers Criteria says: don’t use them here. Same with benzodiazepines like lorazepam (Ativan) for seniors with a history of falls or dementia-they increase the risk of serious injury.

3. Medications That Need Caution

Some drugs aren’t outright banned, but they need careful handling. Dabigatran (Pradaxa), a blood thinner, is one. It’s easier to use than warfarin because it doesn’t need regular blood tests. But for seniors over 75 or those with reduced kidney function, the risk of dangerous bleeding goes up. The criteria says: use it only if the benefits clearly outweigh the risks-and monitor closely.

4. Dangerous Drug Interactions

It’s not just about single drugs. Combinations can be deadly. Taking an anticholinergic like oxybutynin (for overactive bladder) with an opioid like oxycodone can cause severe constipation, urinary retention, and mental fog. The Beers Criteria flags these combinations so prescribers can rethink the plan.

5. Dose Adjustments for Kidney Problems

As we age, kidneys slow down. Many drugs are cleared through the kidneys, so the same dose that’s safe for a 40-year-old can be toxic for a 75-year-old. Gabapentin, used for nerve pain, is a prime example. If kidney function drops below 60 mL/min, the dose must be lowered. Otherwise, it builds up and causes dizziness, drowsiness, and even falls. The 2023 update added clearer dosing guidance for 18 more medications.

What Changed in the 2023 Update?

The 2023 version added 32 new medications and removed 18. Why? Because science moved forward. Some drugs once thought to be risky were found to be safe under certain conditions. Others, newly approved or more widely used, turned out to be more dangerous than expected.For example, the antipsychotic quetiapine was flagged for use in dementia-related psychosis. While it’s still discouraged, the new version added nuance: it may be appropriate for short-term use in cases of severe agitation or aggression when other options have failed. That’s important-because sometimes, the alternative is physical restraint or hospitalization.

Also new: the Alternatives List. This wasn’t in earlier versions. Now, for each flagged medication, the criteria suggests safer options. For insomnia, instead of benzodiazepines, try cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT-I). For chronic pain, consider physical therapy or acetaminophen before opioids. For overactive bladder, pelvic floor exercises may work better than oxybutynin.

How Do Doctors Use It?

Most hospitals and clinics in the U.S. have integrated the Beers Criteria into their electronic health records. When a doctor prescribes a flagged drug, the system pops up a warning. Some systems are smarter-they’ll suggest alternatives or flag interactions before the prescription is even sent.One study showed that when EHR alerts were properly set up, inappropriate prescribing dropped by 37% in just six months. That’s huge. But not every system works well. Some doctors complain about “alert fatigue”-they get so many warnings that they start ignoring them. One primary care doctor reported 12 Beers-related alerts per patient visit. That’s not helpful. It’s overwhelming.

The best results come when pharmacists lead the review. In clinics with pharmacist-led medication therapy management, the number of high-risk prescriptions fell by 28%. Pharmacists are trained to spot these issues, talk to patients, and work with doctors to find better options.

Why Isn’t Everyone Using It?

Despite its benefits, only 41% of primary care practices consistently apply the Beers Criteria. Why?First, time. A typical doctor visit lasts 15 minutes. Reviewing a patient’s full medication list-especially if they’ve seen multiple specialists-takes longer. Many doctors feel pressured to move on.

Second, lack of training. Medical schools don’t always teach geriatric pharmacology well. Many doctors learned their prescribing habits decades ago and haven’t updated them.

Third, patient expectations. Seniors often ask for the same meds they’ve taken for years. “I’ve been taking Benadryl to sleep for 20 years,” they say. Explaining why it’s risky now-and offering a better solution-takes patience and communication.

And then there’s cost. Some alternatives are more expensive. A senior might be told to stop a cheap generic anticholinergic and switch to a non-drug therapy like CBT-I. But if they can’t afford therapy sessions or don’t have access to them, the advice feels unrealistic. As one Harvard researcher pointed out, the Beers Criteria doesn’t address financial barriers-yet 25% of Medicare patients skip doses because they can’t pay.

How Seniors Can Use the Beers Criteria

You don’t need to be a doctor to use this. If you or a loved one are over 65 and taking multiple medications, ask these questions:- Is this medication on the Beers Criteria list?

- Is there a safer alternative?

- Could this drug be causing my dizziness, confusion, or constipation?

- Have we reviewed all my meds together-prescriptions, OTCs, and supplements?

The American Geriatrics Society offers a free mobile app and pocket guide with the full list. It’s updated quarterly. Download it. Bring it to your next appointment. Don’t be afraid to say: “I read this might not be right for me-can we talk about it?”

And remember: stopping a medication isn’t always easy. Some drugs need to be tapered slowly. Never quit cold turkey. Always work with your doctor or pharmacist.

What’s Next?

The AGS is working on the 2026 update, which will add detailed kidney dosing for every medication cleared by the kidneys. They’re also partnering with Google Health to build AI tools that predict which seniors are most at risk for adverse drug events based on their health history, medications, and lab results.Meanwhile, the pharmaceutical industry is responding. Over 23 new “senior-friendly” medications have been developed to replace Beers-listed drugs. The market for these is expected to hit $84 billion by 2027.

But the real win isn’t in new pills. It’s in better prescribing. In fewer falls. In clearer minds. In less time in the hospital. The Beers Criteria isn’t perfect-but it’s the best tool we have to protect older adults from harm that’s entirely preventable.

Is the Beers Criteria only for people in nursing homes?

No. The Beers Criteria applies to all adults aged 65 and older, whether they live at home, in assisted living, or in a nursing facility. It was originally developed for nursing homes, but research showed the same risks exist for seniors living independently. In fact, 23% of community-dwelling seniors are taking at least one medication flagged by the criteria.

Can I still take a medication on the Beers list if my doctor says it’s okay?

Yes. The Beers Criteria is a guide, not a rule. There are exceptions-for example, an antipsychotic might be necessary for severe agitation in dementia, or an NSAID might be the only option for someone with uncontrolled pain who can’t take other meds. The key is that the decision is intentional, documented, and reviewed regularly. If your doctor prescribes a Beers-listed drug, ask why and if there are safer alternatives.

Are over-the-counter drugs included in the Beers Criteria?

Yes. Many of the most dangerous medications for seniors are sold without a prescription. First-generation antihistamines like diphenhydramine (Benadryl) and doxylamine (Unisom) are on the list. Cold medicines, sleep aids, and even some allergy pills contain these. Always check the active ingredients-even if it’s “natural” or “non-drowsy,” it might still have hidden anticholinergic effects.

Why don’t all pharmacies warn me about Beers-listed drugs?

Pharmacies rely on alerts from electronic health records. If your doctor didn’t flag the drug during prescribing, or if the system doesn’t have the latest Beers Criteria loaded, the pharmacy won’t know. Also, some systems only flag drugs prescribed by that pharmacy’s own system. If you get prescriptions from multiple places, gaps happen. Always ask your pharmacist to run a full medication review at least once a year.

Does Medicare require doctors to use the Beers Criteria?

Yes, for certain programs. Medicare Part D requires prescription drug plans to use the Beers Criteria when managing medications for dual-eligible beneficiaries (those on both Medicare and Medicaid). This affects over 12 million people. It doesn’t mean every doctor must use it, but if you’re enrolled in one of these plans, your medication list will be reviewed against the criteria by a pharmacist.

laura Drever

January 14, 2026 AT 10:40Beers Criteria my ass

Gregory Parschauer

January 14, 2026 AT 20:08Let’s be real - this isn’t about patient safety, it’s about liability avoidance dressed up as clinical wisdom. Diphenhydramine? Of course it’s risky. But so is forcing a 78-year-old widow to sit through six weeks of CBT-I when she just wants to sleep without hallucinating her dead husband’s ghost. The system doesn’t care about dignity, only metrics. And now they’re pushing AI to predict who’ll fall? Brilliant. We’ve replaced human judgment with algorithmic paternalism. The real crisis isn’t polypharmacy - it’s that we’ve stopped seeing seniors as people who deserve agency, not just risk scores.

Randall Little

January 16, 2026 AT 16:21So let me get this straight - we’ve got a list that’s updated every three years based on 7,000 studies, yet doctors still prescribe Benadryl like it’s candy? And you’re telling me the solution is ‘ask your pharmacist’? That’s like telling someone with a broken leg to ‘try walking slower.’ The real problem isn’t the list - it’s the culture of prescribing that treats geriatrics like an afterthought. Medical schools still teach pharmacology like it’s 1995. And don’t get me started on how Medicare Part D lets insurers cherry-pick which Beers drugs to flag. This isn’t science. It’s bureaucratic theater.

James Castner

January 16, 2026 AT 19:35It is not merely a matter of pharmacokinetics or even clinical guidelines - it is, at its core, a profound moral reckoning with the way our society values - or rather, devalues - its elderly. The Beers Criteria, in its meticulous, evidence-based structure, serves as a mirror held up to our collective indifference. We have created a system wherein the biological reality of aging - the gradual, inexorable decline of renal function, the diminished hepatic metabolism, the altered blood-brain barrier permeability - is met not with compassion, but with prescription pads and profit-driven formularies. To prescribe an anticholinergic to a frail elder is not merely an error in pharmacology; it is an existential neglect. And yet, we rationalize it with time constraints, with lack of training, with patient preference - all convenient lies that absolve us of the responsibility to truly see, to truly listen, to truly care. The Alternatives List is not a footnote - it is a call to revolution. Not in drugs, but in demeanor. In presence. In humility.

Adam Rivera

January 17, 2026 AT 21:10My grandma’s on three Beers-listed meds and she’s doing great - walks every day, remembers my birthday, still makes her famous apple pie. Doctors aren’t the enemy. Sometimes the meds help more than they hurt. Just because something’s on a list doesn’t mean it’s bad for *your* person. Talk to your provider, don’t just panic because of a blog post. We gotta stop fear-mongering and start personalizing care.

Rosalee Vanness

January 19, 2026 AT 10:50Oh my god, I’ve been screaming this from the rooftops since my dad started taking that damn oxybutynin. He was stumbling around like a drunk toddler, couldn’t remember his own phone number - and we all thought it was just ‘getting old.’ Turns out? Classic anticholinergic fog. We switched him to pelvic floor PT after reading the Alternatives List - no meds, just exercises. Six months later? He’s laughing again. He told me last week, ‘I feel like I got my brain back.’ This isn’t just about avoiding bad drugs - it’s about returning dignity. And yeah, it takes time. And yeah, it’s harder than popping a pill. But when you see someone light up because they’re not foggy anymore? Worth every minute. Please, if you’re caring for someone over 65 - don’t just accept the script. Dig. Ask. Push. You might just save their mind.

lucy cooke

January 21, 2026 AT 06:24How quaint. A list. As if human complexity can be reduced to a bullet-pointed algorithm penned by ivory-tower gerontologists who’ve never held a trembling hand at 3 a.m. The Beers Criteria is the epitome of modern medicine’s narcissism - believing that data can replace wisdom, that guidelines can substitute for love. We have turned the sacred act of healing into a compliance checklist. And now, we outsource our moral failures to AI and EHR alerts? How poetic. The real tragedy isn’t Benadryl - it’s that we’ve forgotten how to sit with the dying, how to hold space for their fear, their confusion, their quiet dignity. The list doesn’t save lives. Presence does. And presence? It’s not billable.

Trevor Davis

January 22, 2026 AT 07:08Look, I get it. The Beers list is important. But let’s not pretend this is some revolutionary breakthrough. My aunt’s pharmacist flagged her lorazepam last year - she’d been on it for 18 years. We tapered slowly. She cried for a week. Then she started sleeping better. No pills. Just routine, sunlight, and a warm blanket. The real win here isn’t the list - it’s the fact that someone finally *listened*. That’s what’s missing. Not knowledge. Connection. I’ve seen too many seniors treated like medical case files. This isn’t about avoiding bad drugs - it’s about not treating people like problems to be solved.

John Tran

January 23, 2026 AT 12:22So the Beers Criteria says avoid NSAIDs in heart failure - okay fine. But what if the alternative is morphine? What if the pain is so bad they can’t breathe? You wanna tell someone with terminal cancer to go do yoga instead? The criteria is great in theory but ignores the brutal reality of end-of-life care. And don’t even get me started on the ‘alternatives’ - CBT-I? For a 90-year-old with dementia and no internet? Who’s gonna pay for that? This list is written by people who’ve never seen a senior on a fixed income trying to choose between insulin and groceries. It’s not guidance - it’s privilege dressed up as science.

Trevor Whipple

January 23, 2026 AT 13:41Uhhh… Benadryl? Really? That’s what you’re worried about? My grandpa’s been on it since Nixon and he’s still driving to bingo. You people are overreacting. It’s not the meds, it’s the doctors who don’t know how to taper. And why are you so obsessed with ‘alternatives’? Who’s gonna pay for all this ‘pelvic floor therapy’? My grandma’s not gonna sit on a damn ball. She wants to sleep. And if Benadryl does it? Let her sleep. Stop overthinking. It’s just a pill. Stop treating old people like lab rats.