How patents drive drug innovation - and why generics matter

Imagine a new drug that can treat a life-threatening disease. It took 12 years, $2.6 billion, and thousands of failed experiments to get it from a lab bench to a pharmacy shelf. Now imagine that same drug becomes available for 85% less money just a few years later. That’s the tension at the heart of patent law in pharmaceuticals: protecting innovation while making medicine affordable.

The U.S. system doesn’t try to pick one side. It’s built to do both. The Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984 is the backbone of this balance. Created by Senators Orrin Hatch and Henry Waxman, it didn’t just tweak the rules - it rewrote the entire game for how brand-name drugs and generics interact.

What patents actually protect in drug development

A pharmaceutical patent gives a company the legal right to be the only one selling a specific drug for 20 years - from the day they file the patent application. But here’s the catch: that 20 years doesn’t mean 20 years on the market.

Drug development takes forever. Clinical trials, FDA reviews, manufacturing setup - all that eats up 8 to 10 years before the drug even hits shelves. So by the time a new drug is approved, the patent might only have 10 to 12 years left. That’s why companies fight so hard to protect every inch of exclusivity.

That’s where patent term restoration comes in. If a drug’s approval was delayed by FDA review, the patent can be extended by up to five years - but only if the total market exclusivity doesn’t exceed 14 years after FDA approval. This isn’t a loophole. It’s a calculated trade: you get a fair shot to recoup your investment, but not forever.

How generics enter the market - legally

Generics don’t wait for patents to expire. They start working on them while the brand drug is still under patent. That’s the genius of the Hatch-Waxman Act. Generic manufacturers can file an application with the FDA years in advance, proving their version is chemically identical and works the same way.

But they can’t sell it yet. So they use something called a Paragraph IV certification. This is their formal notice to the brand company: “We believe your patent is invalid, or our drug doesn’t infringe it.”

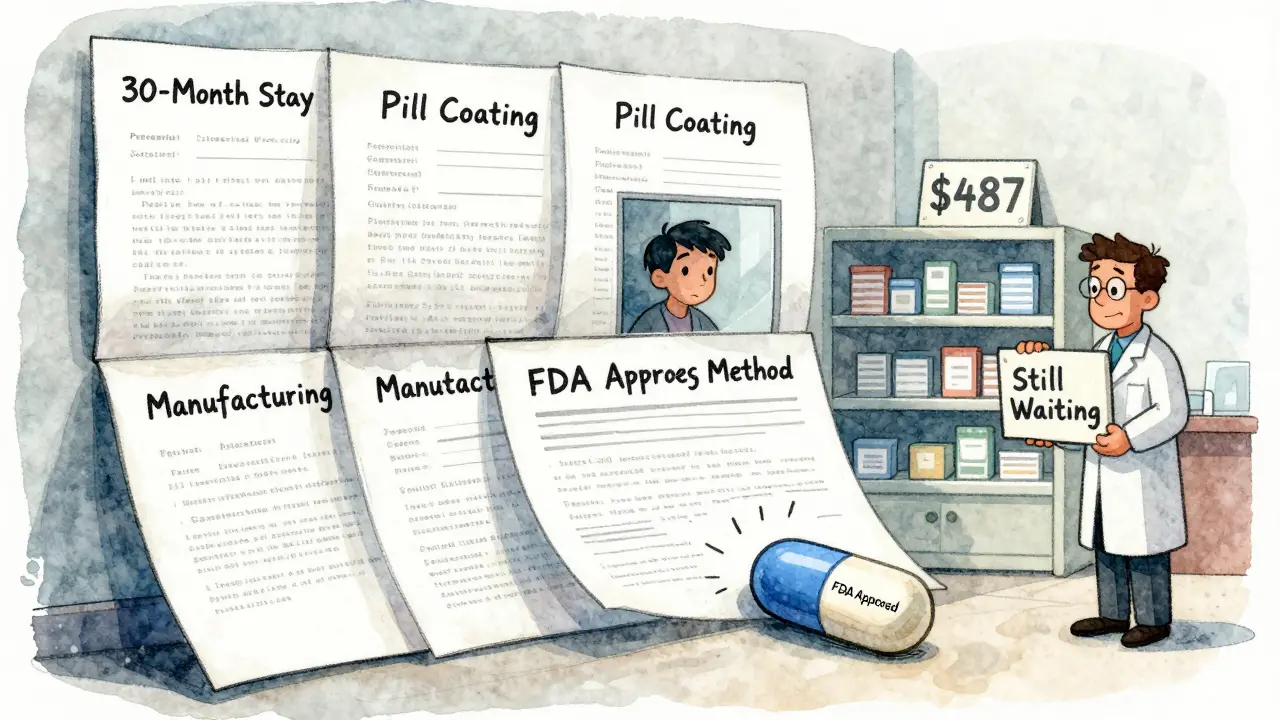

That triggers a legal bomb. The brand company has 45 days to sue for patent infringement. If they do, the FDA can’t approve the generic for 30 months - even if the patent is clearly weak. This 30-month stay gives innovators a guaranteed buffer, no matter the merits of the case.

The 180-day prize: why generics fight for the first shot

The real game-changer? The first generic company to successfully challenge a patent gets 180 days of exclusive market access. No other generics can enter during that time.

Why does that matter? Because of state laws that force pharmacists to substitute generics when available. That means the first generic gets nearly all the business - and can charge a premium, even while undercutting the brand. In some cases, that first mover makes more in 180 days than the brand did in a year.

This incentive is why so many generic companies risk millions in legal fees. They’re not just selling pills - they’re betting on a patent being overturned. And when they win, the savings ripple through the whole system.

The numbers don’t lie: generics save billions

By 2022, over 32,000 generic drugs had been approved in the U.S. They make up 91% of all prescriptions filled - but only 24% of total drug spending.

That’s $373 billion saved every year. A bottle of ibuprofen that once cost $15 under the brand name Brufen now costs under $1. Eli Lilly’s Prozac lost 70% of its U.S. market share the year its patent expired. Annual sales dropped by $2.4 billion overnight.

Each new generic that enters pushes prices down further. After three or four generics are on the market, the price often drops by 90%. That’s not speculation. That’s what happens in real life, every single time.

The dark side: evergreening and patent thickets

But not all patent strategies are about innovation. Some are about delay.

“Evergreening” is when a brand company files new patents on tiny changes - a new pill coating, a different dosing schedule, a slightly altered manufacturing process. These aren’t breakthroughs. They’re legal tweaks designed to extend exclusivity.

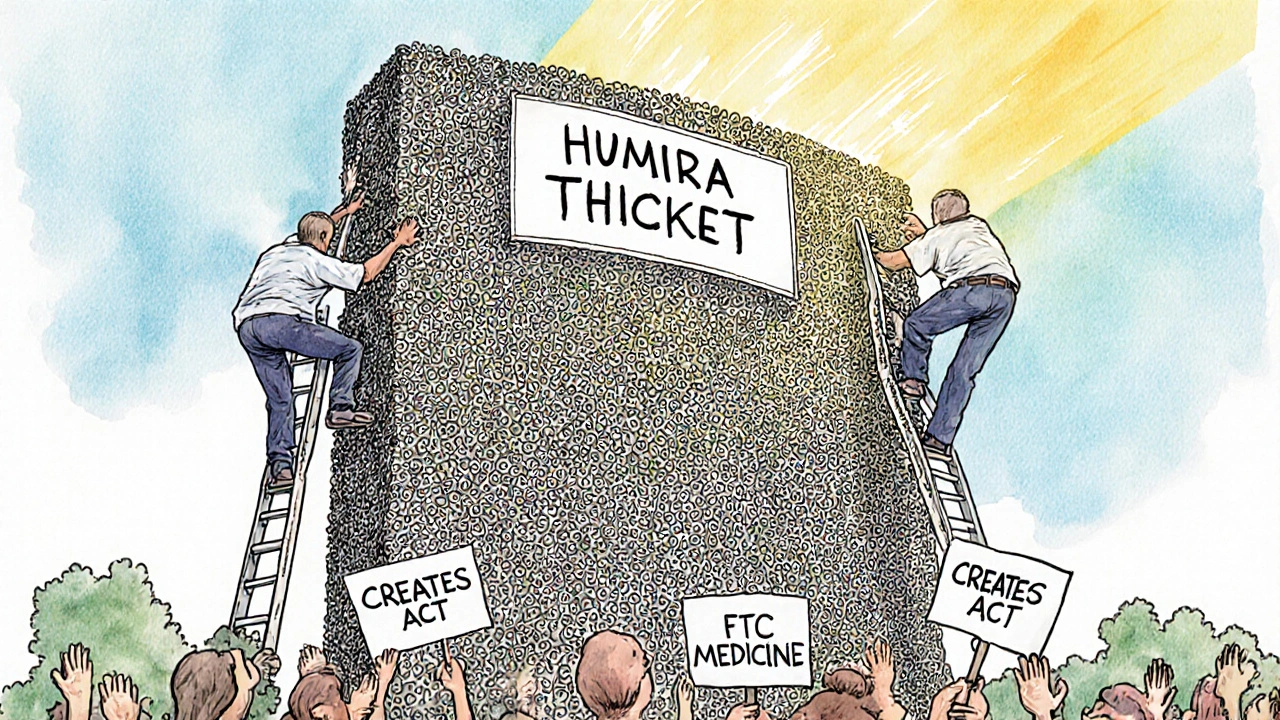

Humira, the arthritis drug, had 241 patents across 70 families. That’s not protection. That’s a wall. It kept biosimilars out of the U.S. until 2023 - even though they were available in Europe since 2018.

The European Commission calls this abuse of dominance. The FTC calls it anti-competitive. And it’s why Congress passed the CREATES Act in 2022 - to stop brand companies from blocking generic makers from getting samples needed for testing.

Pay-for-delay: the settlement that hurts patients

Here’s another twist: sometimes, the brand company doesn’t sue. They pay the generic company to stay away.

These “pay-for-delay” deals are legal loopholes. The brand pays the generic millions to delay launching its cheaper version. The FTC estimates these deals cost U.S. consumers $3.5 billion a year.

It’s a perverse incentive: why risk a patent fight when you can just get paid to sit on the sidelines? That’s why lawmakers are pushing the Preserve Access to Affordable Generics Act - to ban these settlements outright.

Where the system stands today

The Hatch-Waxman Act is still the rulebook. In 2023, 97% of generic applications still used the Paragraph IV process. The average time to resolve a patent dispute? 28.7 months.

Generics still enter faster than ever - but not as fast as they could. The average delay between patent expiry and generic launch has grown from 2.1 years in 2005 to 3.6 years in 2020. That’s because litigation has become more complex, more expensive, and more strategic.

Biologics - complex drugs made from living cells - are the next frontier. The 2017 Amgen v. Sandoz case threw a wrench into the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act. Courts are still figuring out how to handle patent disputes for these drugs. The rules are still being written.

Who wins? Who loses?

Brand companies argue they need strong patents to justify spending $83 billion a year on R&D. Without that, they say, no new cancer drugs, no new antibiotics, no new treatments.

Generic makers counter: we’ve saved $2.2 trillion since 2010. We’re not stealing innovation - we’re making it accessible.

The truth? Both are right. Innovation needs protection. But access needs urgency.

The system isn’t perfect. It’s messy, litigious, and full of loopholes. But it still works - for patients, for payers, and for the next drug that might save a life.

What’s next for patent law and generics?

The pressure is mounting. Prescription drug spending hit $621 billion in 2022 - 22% of all U.S. healthcare costs. Lawmakers are watching. Courts are watching. Patients are watching.

Expect more fights over patent validity. More scrutiny of evergreening. More attempts to close pay-for-delay deals. And more pressure to speed up generic approval for complex drugs.

One thing won’t change: as long as drugs cost billions to make, patents will be the shield. And as long as people need affordable medicine, generics will be the sword.

How long does a pharmaceutical patent last?

A pharmaceutical patent lasts 20 years from the date it’s filed. But because drug development takes 10-12 years on average, the actual time a company has to sell the drug without competition is usually only 8-10 years. The Hatch-Waxman Act allows for patent term restoration of up to five years to make up for delays in FDA approval, but total market exclusivity can’t exceed 14 years after approval.

Why do generic drugs cost so much less?

Generic drugs cost 80-85% less because they don’t need to repeat expensive clinical trials. They prove they’re bioequivalent to the brand drug - meaning they work the same way in the body. The brand company already paid the $2.6 billion R&D cost. Generics just replicate the formula, which costs a fraction of the original investment.

What is the Orange Book and why does it matter?

The Orange Book is the FDA’s official list of approved drugs and their associated patents. Brand companies must list every patent they believe covers their drug. Generics use this list to decide whether to challenge a patent before investing in development. It’s the roadmap for legal battles - and the key to when generics can enter the market.

Can a generic drug be approved before a patent expires?

Yes - but only if the generic company files a Paragraph IV certification challenging the patent’s validity or claiming non-infringement. This triggers a lawsuit from the brand company, which can delay FDA approval by up to 30 months. If the generic wins the case or the patent is invalidated, they can launch immediately. Many generics use this strategy to enter the market early.

What’s the difference between a generic and a biosimilar?

Generics are exact copies of small-molecule drugs made from chemicals. Biosimilars are similar - but not identical - copies of complex biologic drugs made from living cells. Because biologics are harder to replicate, biosimilars require more testing and face longer approval times. The rules for biosimilars are still evolving, especially after court rulings like Amgen v. Sandoz.

Dana Dolan

November 19, 2025 AT 11:40Brian Rono

November 20, 2025 AT 09:11seamus moginie

November 21, 2025 AT 11:32Ellen Calnan

November 21, 2025 AT 23:55Richard Risemberg

November 23, 2025 AT 12:45Andrew Montandon

November 23, 2025 AT 14:19Sam Reicks

November 23, 2025 AT 22:04Chuck Coffer

November 24, 2025 AT 09:04Marjorie Antoniou

November 25, 2025 AT 20:19Andrew Baggley

November 27, 2025 AT 04:50Codie Wagers

November 27, 2025 AT 07:16Paige Lund

November 28, 2025 AT 15:02