Hyperkalemia Risk Calculator

When you take an ACE inhibitor for high blood pressure or heart failure, and your doctor adds a potassium-sparing diuretic to help with fluid retention, it might seem like a smart combo. But here’s the hidden danger: together, they can push your potassium levels into dangerous territory - and you might not feel a thing until it’s too late.

How ACE Inhibitors and Potassium-Sparing Diuretics Work

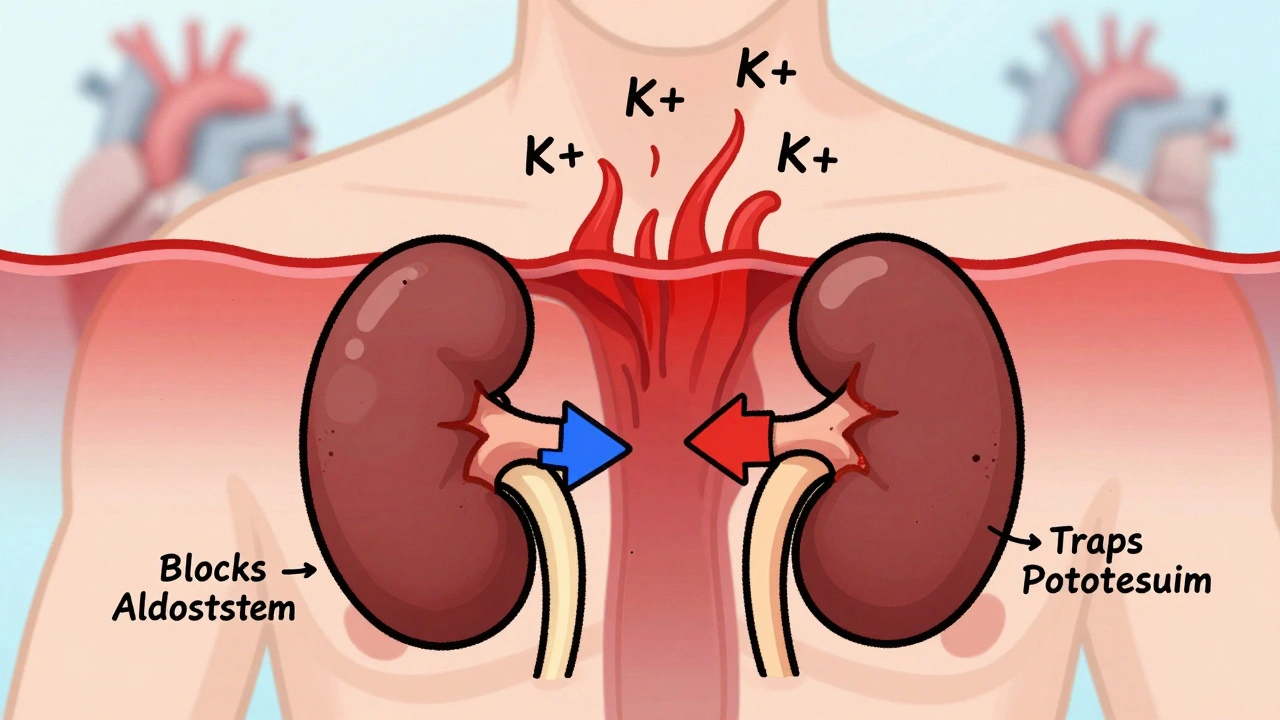

ACE inhibitors - like lisinopril, enalapril, or ramipril - block a hormone called angiotensin II. That helps relax blood vessels and lower blood pressure. But there’s a side effect you don’t hear much about: they also reduce aldosterone, a hormone that tells your kidneys to flush out potassium. Less aldosterone means potassium stays in your blood.

Potassium-sparing diuretics - such as spironolactone, eplerenone, amiloride, or triamterene - do something similar but in a different way. Spironolactone and eplerenone block aldosterone receptors directly. Amiloride and triamterene shut down the sodium channels in your kidneys that normally pull potassium out with urine. So instead of helping you pee out extra salt and water, they keep potassium in.

Put them together, and you’ve got a double hit on your kidneys’ ability to remove potassium. It’s not just additive - it’s multiplicative. Your body can’t compensate fast enough, and potassium builds up.

What Is Hyperkalemia - And Why It’s Dangerous

Hyperkalemia means your blood potassium level is above 5.0 mmol/L. Normal is 3.5 to 5.0. When it hits 6.0 or higher, your heart’s electrical system starts to misfire. You might get palpitations, muscle weakness, or feel oddly tired. But often, there are no symptoms at all.

That’s the real danger. Without warning, high potassium can trigger ventricular fibrillation - a chaotic, deadly heart rhythm. In severe cases, it can stop your heart entirely. Studies show that hyperkalemia causes sudden death in up to 10% of hospitalized patients with levels above 6.5 mmol/L.

The risk isn’t equal for everyone. People with kidney disease, diabetes, heart failure, or who are older are far more vulnerable. Your kidneys are already struggling to filter waste - adding these drugs pushes them past their limit.

The Numbers Don’t Lie: How Common Is This?

In 1998, a landmark study of over 1,800 patients found that 11% of those taking ACE inhibitors developed hyperkalemia. But when potassium-sparing diuretics were added, the risk jumped to nearly 30% in some groups.

More recent data from the REIN study showed that in patients with chronic kidney disease, hyperkalemia rose from 4.2% with ACE inhibitors alone to 18.7% when spironolactone was added. That’s more than four times higher.

And it’s not rare. In the U.S., about 45 million people take ACE inhibitors. Roughly 12 million of them also take a potassium-sparing diuretic. That means over 5 million people are walking around with a ticking time bomb in their blood - and many don’t even know it.

Who’s at Highest Risk?

Not everyone needs to panic. But if you have any of these, your risk is much higher:

- eGFR below 60 mL/min/1.73 m² (sign of reduced kidney function)

- Baseline potassium above 4.5 mmol/L

- Diabetes

- Heart failure

- Age over 65

- Taking other drugs that raise potassium - like NSAIDs, heparin, or trimethoprim

A simple scoring system used by the Cleveland Clinic gives you points for each risk factor. If you score 4 or more, you’re in the high-risk zone. That means you need close monitoring - not just a one-time check.

When and How to Check Your Potassium

Guidelines are clear: if you’re starting an ACE inhibitor plus a potassium-sparing diuretic, don’t wait. Test your potassium within 1 week. Then again at 2 weeks and 4 weeks. After that, every 3 months if you’re stable.

If your eGFR is below 30 - meaning your kidneys are severely impaired - check weekly at first. That’s not optional. That’s life-saving.

And here’s the kicker: 78% of hyperkalemia cases happen in the first 3 months after starting the combo. Peak risk? Weeks 4 to 6. That’s when your body is still adjusting. Many doctors miss this window because they assume the patient is fine if they feel okay.

What to Do If Potassium Is Too High

If your potassium is between 5.1 and 5.5 mmol/L:

- Review your diet. Bananas, oranges, potatoes, tomatoes, spinach, and salt substitutes are loaded with potassium. Cutting these back can lower your levels by 0.3 to 0.6 mmol/L.

- Consider switching from spironolactone to triamterene - it’s weaker and less likely to cause spikes.

- Add a thiazide diuretic like hydrochlorothiazide (12.5-25 mg daily). It helps flush out potassium without losing the heart benefits of your ACE inhibitor.

If your potassium is above 5.5 mmol/L:

- Don’t stop your ACE inhibitor unless your doctor says so. These drugs cut heart failure deaths by 23% and post-heart attack deaths by 26%. You don’t want to trade one risk for another.

- Ask about potassium binders like patiromer (Veltassa) or sodium zirconium cyclosilicate (Lokelma). These newer drugs trap potassium in your gut and remove it in stool. They let you keep your life-saving meds while lowering potassium safely.

- Get a nephrologist involved. Only 22% of patients with potassium above 6.0 get specialist care - but they’re the ones who need it most.

Why Many Doctors Miss This

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: even though guidelines have been clear for years, most primary care doctors don’t follow them.

A 2023 AHA statement found that 41% of primary care physicians lack confidence managing hyperkalemia. Only 28% check potassium regularly in high-risk patients. And 33% of patients with severe hyperkalemia (above 6.0) had no follow-up within 7 days.

Why? Time. Lack of training. Assumptions that “it’s not that common.” But it is. And the cost? In the U.S. alone, hyperkalemia-related hospitalizations cost $4.8 billion a year. Each episode averages over $11,000.

It’s preventable. But only if you - and your doctor - are paying attention.

New Hope: Better Tools and Alternatives

There’s good news on the horizon. SGLT2 inhibitors - like dapagliflozin - originally for diabetes, now show they reduce hyperkalemia risk by 32% in patients on ACE inhibitors. That’s a game-changer. Now, some patients are getting a triple combo: ACE inhibitor + SGLT2 inhibitor + low-dose potassium-sparing diuretic. It’s safer than it sounds.

And digital tools are helping. Apps that track dietary potassium intake cut hyperkalemia episodes by 27% compared to standard care. If your doctor doesn’t mention them, ask. You can log your food, get alerts, and avoid hidden potassium in processed foods - which often contain potassium chloride as a salt substitute.

Future tech is coming too. Point-of-care potassium meters - like the ones being tested by Kalium Diagnostics - could let you check your levels at home, like a glucose monitor. And someday, genetic testing for WNK1 gene variants might tell you if you’re naturally prone to high potassium, letting doctors personalize your meds from day one.

Bottom Line: Stay Informed, Stay Safe

ACE inhibitors and potassium-sparing diuretics are powerful, life-saving drugs. But together, they’re a minefield if not handled right. The risk of hyperkalemia is real, silent, and deadly - but it’s also predictable and preventable.

If you’re on this combo:

- Know your numbers. Ask for your latest potassium and eGFR results.

- Get tested early and often - especially in the first 6 weeks.

- Watch your diet. Skip the salt substitutes and limit high-potassium fruits and veggies.

- Don’t stop your meds without talking to your doctor.

- Ask about potassium binders or SGLT2 inhibitors if your levels keep rising.

This isn’t about fear. It’s about control. You’re not powerless. With the right checks and conversations, you can keep your heart healthy - without letting your potassium sneak up on you.

parth pandya

December 2, 2025 AT 09:15So i was on lisinopril + spironolactone for like 8 months n my potassium hit 5.8 n i felt fine. no symptoms. doc said "oh u r fine" n didn't check again for 3 months. turns out i was one heartbeat away from cardiac arrest. now i use a potassium binder. dont trust "you feel okay" logic. your heart dont care how you feel.

Charles Moore

December 3, 2025 AT 09:56This is such an important post. I’ve seen too many patients get discharged after a heart failure admission with this combo and no follow-up plan. The real tragedy isn’t the drug interaction-it’s the system that lets it slide. A simple potassium test takes 5 minutes and costs $12. Why are we waiting for someone to code before we act?

Primary care is drowning. But this isn’t an excuse. We owe our patients better.

Gavin Boyne

December 5, 2025 AT 02:43Let me get this straight-we’re giving people two drugs that both say "keep potassium" and then acting shocked when their blood turns into a potassium smoothie?

Also, the fact that 41% of PCPs "lack confidence" managing this is less a training gap and more a systemic failure. You don’t need to be a nephrologist to know: if two things make potassium go up, don’t give them together without checking.

And yes, I’m talking to you, Dr. Google-diagnosed hypertensives who think bananas are a breakfast food.

sagar bhute

December 5, 2025 AT 03:16Typical western medicine nonsense. You take a pill to fix a symptom, then another pill to fix the side effect of the first pill, then another pill to fix the side effect of the second pill. Meanwhile, your kidneys are screaming. Why not just eat less salt, walk more, and stop pretending drugs are magic? This is why people die in hospitals-they’re drowning in prescriptions, not healing.

shalini vaishnav

December 6, 2025 AT 16:12Of course Americans don’t know how to manage this-your diet is pure potassium bombs. Bananas, sweet potatoes, coconut water, salt substitutes-you people treat your bodies like garbage disposals. In India, we know real food doesn’t come in packets with potassium chloride listed as ingredient #2. This isn’t a drug problem. It’s a cultural problem.

Gene Linetsky

December 7, 2025 AT 05:59They’re hiding something. ACE inhibitors were pushed by Big Pharma after the 1990s calcium channel blocker scandals. Potassium-sparing diuretics? Designed to look safe but they’re slow poison. The FDA knows. The AMA knows. That’s why they only test potassium at "3 months"-because if they tested weekly, the death toll would be public. You think they want you to know about the 5 million ticking bombs? No. They want you to keep buying the pills.

Ignacio Pacheco

December 7, 2025 AT 11:48Wait-so if I’m on this combo and my potassium is 5.2, do I just… keep taking it? Or do I panic? The article says "don’t stop your meds" but also says "it’s a ticking time bomb." So… what’s the actual move here? I’m confused. Is this like driving with one foot on the gas and one on the brake?

Jim Schultz

December 8, 2025 AT 19:02Let’s be real: if your eGFR is below 60, you shouldn’t even be on spironolactone. Period. End of story. And if your doctor is still prescribing this combo without checking potassium every 2 weeks? They’re not your doctor-they’re a liability. I’ve seen 70-year-olds on this combo with CKD and no labs for 6 months. That’s not negligence. That’s malpractice with a smile.

Kidar Saleh

December 9, 2025 AT 04:19I’ve worked in NHS clinics for 18 years. I’ve watched this exact scenario play out-over and over. A man with heart failure, on lisinopril, gets prescribed spironolactone for edema. No baseline potassium. No follow-up. Three weeks later, he’s in A&E with a flatline rhythm. His wife says, "He was fine yesterday."

We don’t need more drugs. We need better systems. A simple automated alert in the EHR when these two are prescribed together? That would save lives. But no. We still rely on tired GPs remembering to check a number they never learned to interpret.

Chloe Madison

December 9, 2025 AT 16:59YOU CAN DO THIS. Seriously. This isn’t a death sentence-it’s a call to be proactive. Ask for your labs. Track your food. Use an app. Talk to your pharmacist. You are not powerless. You are not a victim of your meds. You are the CEO of your health. And if your doctor isn’t listening? Find one who will. You deserve to live-without fear, without surprises. This post? It’s your power-up. Use it.

Vincent Soldja

December 9, 2025 AT 18:55Makenzie Keely

December 11, 2025 AT 06:41Thank you for this. As a nurse practitioner, I’ve seen too many patients come in with potassium levels over 6.0-no symptoms, no prior labs, no follow-up plan. The real issue? We’re treating this like a lab anomaly instead of a life-threatening emergency. And yes-SGLT2 inhibitors are a game-changer. I’ve switched three patients to dapagliflozin + low-dose spironolactone, and their potassium dropped 0.8 points without losing cardiac protection. Also-yes, please use potassium-tracking apps. My patients who did saw a 40% drop in ER visits. Knowledge is power. And power saves lives.

Francine Phillips

December 12, 2025 AT 23:37