When a new biologic drug hits the market, it doesn’t just cost a lot-it’s protected by a legal shield that can keep cheaper versions off shelves for over a decade. Unlike generic pills, which can appear within years of a brand-name drug’s launch, biosimilars face a maze of patents, exclusivity periods, and lawsuits that delay their entry. In the U.S., the clock starts ticking the day the FDA approves a biologic like Humira or Enbrel. But even after that, patients won’t see cheaper alternatives for 12 years.

Why 12 Years? The BPCIA Explained

The Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA), passed in 2010, was meant to balance innovation with competition. It gave drugmakers a 12-year window of market exclusivity, during which the FDA can’t approve any biosimilar. That’s longer than most countries offer. In Europe, it’s 10 years of data protection plus one year of market exclusivity-11 total. Japan and South Korea offer similar but shorter windows. The U.S. stands out for its length, and the impact is real: patients pay far more for longer. But the 12 years aren’t all the same. The first four years are a hard lock: no biosimilar company can even submit an application. After that, they can file-but the FDA still can’t approve anything until year 12. That means companies spend years preparing applications, running tests, and waiting, while the original drug keeps raking in billions. By the time a biosimilar finally gets the green light, the original drug’s patent life has often been stretched even further through legal tactics.The Patent Dance: A Legal Maze That Delays Access

Even after a biosimilar applicant files, they’re pulled into something called the “patent dance.” It’s not a dance at all-it’s a complex, multi-step legal negotiation required under the BPCIA. Within 20 days of the FDA accepting the biosimilar application, the applicant must hand over confidential manufacturing details to the original drugmaker. The original company then has 60 days to list every patent they think might be infringed. The biosimilar maker gets another 60 days to respond with legal arguments on why those patents are invalid or don’t apply. Then, both sides have 15 days to try to agree on which patents to litigate immediately. This process sounds fair. But in practice, it’s been weaponized. Companies like AbbVie, maker of Humira, filed over 160 patents on the same drug-many covering minor formulation changes, delivery devices, or dosing schedules. These weren’t groundbreaking innovations; they were legal fences. Each patent added another layer of litigation, pushing back biosimilar entry by years. In some cases, biosimilar makers settled just to avoid the cost of fighting 50+ patents at once. The Supreme Court weighed in on this in 2017, ruling that skipping the patent dance wasn’t illegal-but it didn’t stop the abuse.Costs That Hurt Patients

The delay isn’t just a legal issue-it’s a financial crisis for patients. Humira’s list price in the U.S. jumped 470% between 2012 and 2022. In Europe, where biosimilars entered in 2018, prices stayed flat. The same pattern holds for Enbrel, Remicade, and other top-selling biologics. Patients with autoimmune diseases, cancer, or rare conditions often face out-of-pocket costs of thousands per month. Many skip doses or stop treatment entirely because they can’t afford it. A 2022 survey by the National Community Pharmacists Association found that 63% of pharmacists had patients who abandoned biologic therapy due to cost. Doctors at Memorial Sloan Kettering reported that U.S. patients paid up to 300% more than Europeans for the same treatment. That’s not just a pricing difference-it’s a life-or-death gap.

Biosimilars Are Harder (and More Expensive) to Make

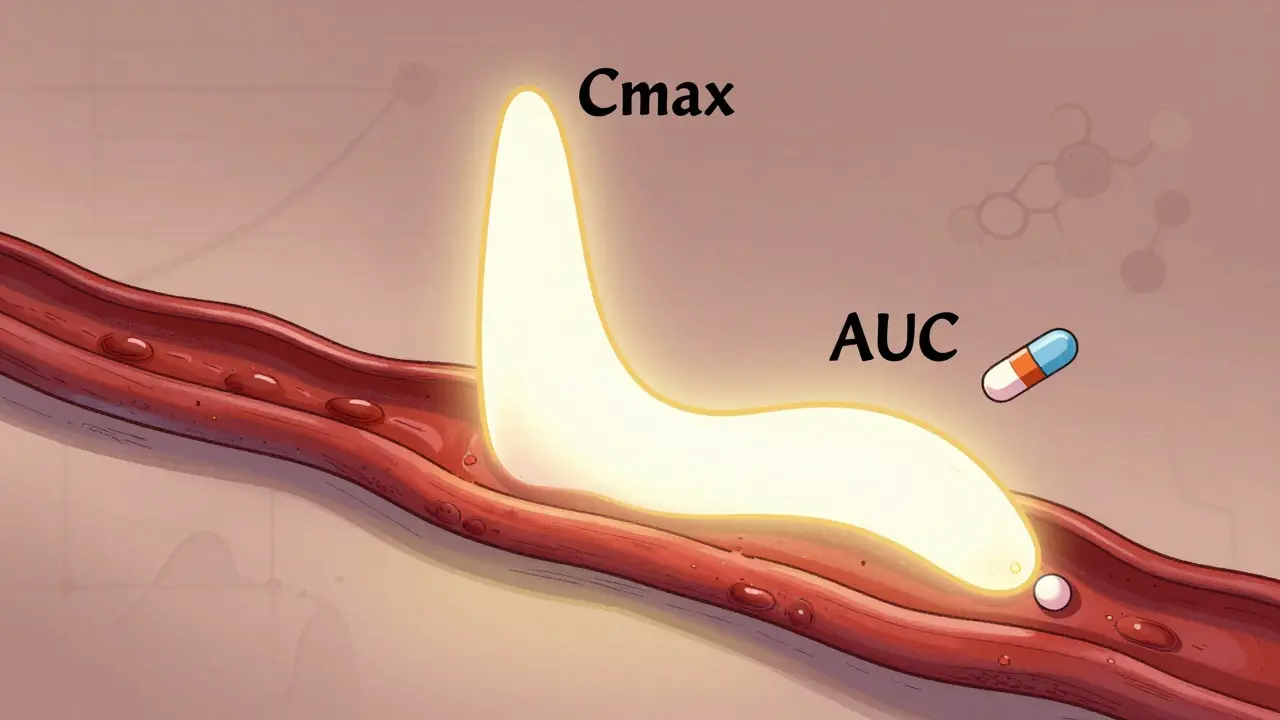

Making a biosimilar isn’t like copying a pill. Biologics are made from living cells-complex proteins that are sensitive to tiny changes in temperature, pH, or manufacturing conditions. A small tweak can alter how the drug works in the body. That’s why regulators require more than just chemical analysis. Biosimilar makers must prove “high similarity” and “no clinically meaningful differences” in safety, purity, and potency. That means running analytical studies, pharmacokinetic tests, and sometimes full clinical trials. The cost? Between $100 million and $250 million, depending on complexity. It takes five to ten years. Compare that to a generic small-molecule drug, which costs $1-2 million and takes two years to develop. The high barrier means fewer companies are willing to enter the market. Even when patents expire, many biosimilar developers walk away because the projected sales don’t justify the investment.The Biosimilar Void: 118 Drugs, But Only 12 in Development

Between 2025 and 2034, 118 biologics will lose patent protection in the U.S.-a $234 billion market opportunity. But according to IQVIA, only 12 of those drugs currently have biosimilars in development. Why? Three big reasons:- Low sales potential: Some biologics treat rare diseases. Even if they’re expensive, the patient pool is small. Developers don’t see enough return.

- Patent thickets: If a drug has 100+ patents, the legal risk is too high for smaller companies.

- Molecular complexity: Antibody-drug conjugates, bispecific antibodies, cell therapies, and gene therapies are incredibly hard to copy. None of the 16 complex biologics set to expire between 2025 and 2034 have biosimilars in the pipeline.

What’s Being Done? Not Enough

The FDA has tried to help. Their 2022 Biosimilars Action Plan promised better communication, faster approvals, and more support for developers. But progress has been slow. Since 2015, the U.S. has approved only 38 biosimilars. Europe, with a smaller population, has approved 88. The U.S. system is still tilted toward the original makers. Legislative efforts like the Biosimilars User Fee Act of 2022 aimed to speed things up but stalled in Congress. Without policy changes, the market will keep favoring big pharma. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that if barriers are lowered, biosimilars could save the U.S. healthcare system $158 billion over the next decade. Under current conditions? Only $71 billion.What’s Next?

The next few years will be critical. As more biologics hit their 12-year mark, the pressure to approve biosimilars will grow. But without changes to how patents are used and how developers are supported, the U.S. will continue to lag behind the rest of the world. Patients will keep paying more. Doctors will keep watching their patients skip treatments. And the gap between what’s possible and what’s available will keep widening. The science is ready. The need is urgent. The question isn’t whether biosimilars can enter the market-it’s whether the system will let them in before it’s too late.How long does a biologic have patent protection in the U.S.?

In the U.S., biologic drugs get 12 years of market exclusivity from the date of FDA approval, as set by the BPCIA. During the first four years, no biosimilar application can even be submitted. After that, applications can be filed-but the FDA can’t approve any biosimilar until the 12-year mark is reached. This period can be extended by six months if the drugmaker completes pediatric studies.

Can biosimilars enter the market before the 12-year exclusivity ends?

No-not legally. The FDA is prohibited from approving a biosimilar until 12 years after the reference biologic’s approval date. Even if a biosimilar company finishes its application early, the FDA must wait. Some companies have tried to challenge this through litigation or by arguing patent invalidity, but the 12-year clock remains the legal floor.

Why are biosimilars more expensive to develop than generic drugs?

Biologics are made from living cells, not chemicals. Their structure is far more complex, and tiny changes in manufacturing can affect how they work in the body. To prove similarity, developers must run extensive analytical tests, pharmacokinetic studies, and sometimes clinical trials. This process costs $100 million to $250 million and takes 5-10 years, compared to $1-2 million and 2 years for a generic small-molecule drug.

What is the patent dance, and why does it delay biosimilars?

The patent dance is a legal process under the BPCIA where a biosimilar applicant must share its application and manufacturing data with the original drugmaker. The drugmaker then lists patents it believes are infringed, and both sides negotiate which ones to litigate. In practice, innovator companies use this process to file dozens or even hundreds of patents, forcing biosimilar makers into expensive, multi-year lawsuits. Many settle just to avoid the cost, delaying market entry.

Why are so few biosimilars in development for orphan drugs?

Orphan drugs treat rare diseases with small patient populations. Even if they’re expensive, the potential sales volume is low, making it hard for developers to recoup the $100+ million investment needed. As a result, 88% of expiring biologics with orphan status have no biosimilars in development, leaving patients with few affordable options.

Ted Conerly

January 9, 2026 AT 23:52The 12-year exclusivity window is a joke. In Europe, they get biosimilars in 10-11 years and prices drop by 70%. Here, patients are held hostage while CEOs cash in. It’s not innovation-it’s rent-seeking disguised as IP protection.

neeraj maor

January 11, 2026 AT 00:13Let’s be real-this isn’t about patents. It’s about the FDA being captured by Big Pharma. The same people who wrote the BPCIA are now on pharma boards. You think the 160 patents on Humira were accidental? Nah. This is engineered monopoly capitalism. The government’s just the enforcer.

McCarthy Halverson

January 11, 2026 AT 18:35Biosimilars cost way more to make. That’s just science. You can’t cut corners on living cells.

Dwayne Dickson

January 13, 2026 AT 09:34While the structural inefficiencies of the BPCIA are well-documented, one must also acknowledge the non-trivial regulatory burden imposed by the requirement for analytical comparability, pharmacokinetic bridging, and immunogenicity assessments-each of which demands a level of analytical rigor that generic small-molecule drugs simply do not. The cost differentials are not arbitrary; they are a direct consequence of molecular complexity and biological variability.

Christine Milne

January 13, 2026 AT 11:10Why should Americans subsidize global drug affordability? Europe and India get cheaper meds because they don’t invest in R&D. We fund the breakthroughs-they free-ride. If biosimilars hurt profits, let them innovate or shut up.

Jake Kelly

January 14, 2026 AT 02:34I get why this is frustrating, but we also need to protect the companies that take the risks to develop these drugs in the first place. It’s a balance, not a battle.

Mario Bros

January 14, 2026 AT 14:4512 years? Bro, my insulin costs $300 a vial. If this is what 'innovation' looks like, I’d rather have a broken system and a working body.

Michael Marchio

January 15, 2026 AT 18:22It’s not just the patents-it’s the entire ecosystem. The FDA’s approval process for biosimilars is slower than molasses in January, and the legal costs are so high that even companies with deep pockets hesitate. And don’t get me started on how the orphan drug designation, meant to help the rarest of the rare, has become a loophole for companies to lock down markets with no competition, no matter how small the patient pool. It’s not just greedy-it’s systematically cruel.

Kunal Majumder

January 16, 2026 AT 22:31India makes generics like candy. But biosimilars? That’s a whole other level. We’re trying, but the US market is too risky. If the rules were clearer and the lawsuits less scary, we’d be all over it.

chandra tan

January 18, 2026 AT 09:07Back home in Kerala, we get insulin for $2. Here? $300. No joke. The science is the same. The only thing different is the greed.

Bradford Beardall

January 18, 2026 AT 22:21Wait-so if the patent dance is optional now, why are companies still doing it? Isn’t that just voluntarily throwing money into a legal black hole?

Paul Bear

January 19, 2026 AT 22:56The notion that biosimilars are somehow ‘cheaper’ is a misrepresentation. The manufacturing, quality control, and clinical validation protocols are not merely scaled-up generics-they are distinct, high-fidelity biological processes requiring ISO-certified bioreactors, single-use systems, and real-time analytics. The $100M-$250M cost is not inflated-it’s actuarially sound. To suggest otherwise is to misunderstand biopharmaceutical science at a fundamental level.

Ashlee Montgomery

January 21, 2026 AT 15:36If we’re protecting innovation, why does it take 12 years to let others build on it? Innovation shouldn’t mean monopoly. It should mean progress. And right now, progress is being held hostage by legal technicalities and profit margins.

Ritwik Bose

January 23, 2026 AT 13:13Global health equity is not a slogan-it’s a moral imperative. When a child in rural India gets life-saving treatment for $5 while an American parent chooses between rent and insulin, we are failing as a civilization. The science is here. The will is not.

Jake Nunez

January 24, 2026 AT 22:46Big Pharma’s playbook is simple: patent everything, sue everyone, and call it innovation. The real innovation is in how they turn human suffering into quarterly earnings reports.