After a kidney transplant, your body doesn’t know the new organ isn’t supposed to be there. It sees it as an invader and tries to attack it. That’s where tacrolimus, mycophenolate, and steroids come in. These three drugs form the backbone of immunosuppression for most kidney transplant patients worldwide. They don’t cure rejection-they stop it before it starts. But they’re not magic pills. They come with trade-offs, side effects, and complex rules you need to follow every single day.

Why Three Drugs? The Science Behind the Combo

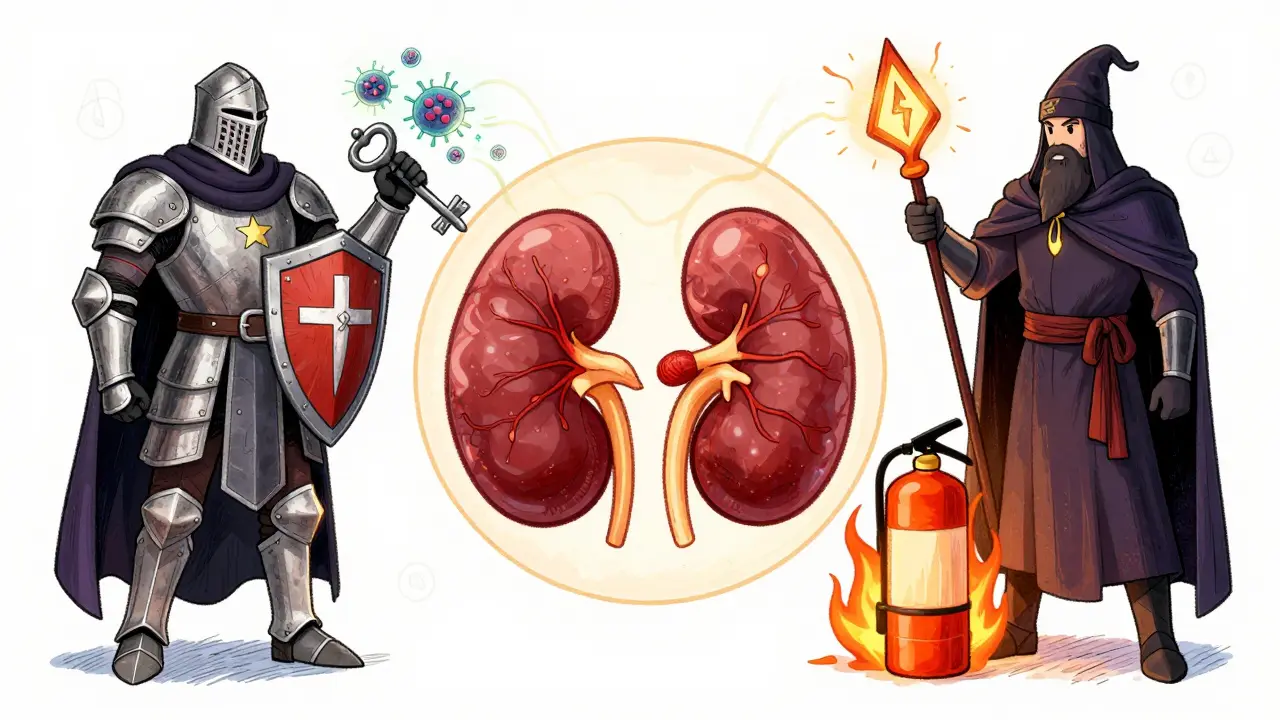

Using just one immunosuppressant isn’t enough. Your immune system is too smart. It finds ways around single drugs. That’s why doctors use a triple combination: each one hits a different part of the immune response. Think of it like locking three different doors to keep intruders out.

Tacrolimus blocks a key signaling protein called calcineurin. Without it, T-cells-your body’s main attack force-can’t activate. Mycophenolate stops white blood cells from multiplying by cutting off their energy supply. Steroids (usually prednisone or methylprednisolone) calm down the whole system like a fire extinguisher for inflammation. Together, they’re more than the sum of their parts.

Back in the 1990s, when this combo was first tested, rejection rates dropped from over 20% to under 10%. That was a game-changer. A 1998 study showed patients on tacrolimus + mycophenolate + steroids had just 8.2% acute rejection, compared to 21% with tacrolimus and steroids alone. That’s a 61% drop. No other single drug could do that. That’s why this trio became the global standard.

Tacrolimus: The Powerhouse with a Narrow Margin

Tacrolimus (also known as FK506) is the most potent of the three. It’s taken twice daily, usually in the morning and evening. The goal? Keep blood levels between 5 and 10 ng/mL in the first year. Too low? Rejection risk spikes. Too high? You risk kidney damage, shaking hands, headaches, or even seizures.

Here’s the catch: everyone absorbs tacrolimus differently. Two people taking the same dose can have wildly different blood levels. That’s why regular blood tests are non-negotiable. In the early months, you might get tested twice a week. Over time, it tapers to monthly, then every few months.

Food, other medications, and even grapefruit juice can mess with how your body handles tacrolimus. Proton pump inhibitors (like omeprazole) can lower its absorption. Antibiotics? They might spike levels. Your pharmacist needs to know every pill you take-even over-the-counter ones.

Long-term, tacrolimus increases your risk of developing diabetes after transplant. About 18-21% of patients end up with post-transplant diabetes. It’s not guaranteed, but it’s common enough that doctors monitor your fasting blood sugar closely. It also raises cholesterol and can cause tremors or trouble sleeping. Still, compared to the old drug cyclosporine, it causes less facial hair and gum swelling. That’s why most centers switched to it.

Mycophenolate: The Gut-Friendly Drug That Isn’t

Mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) is sold under brand names like CellCept. It’s usually dosed at 1 gram twice a day. But here’s the reality: about 1 in 4 patients can’t handle it. Diarrhea, nausea, vomiting-these side effects are so common that many people end up reducing their dose or stopping it entirely.

Why does this happen? Mycophenolate hits fast-dividing cells. That includes immune cells-and the cells lining your gut. It’s not a bug, it’s a feature. But that feature makes life hard for some. If you’re throwing up or having watery stools for days, your doctor might drop the dose to 500 mg twice a day. If that doesn’t help, they might switch you to mycophenolic acid (Myfortic), which is easier on the stomach for some.

Another risk? Low white blood cell count. About 15% of patients develop leukopenia. That means your body can’t fight infections as well. Your blood will be checked weekly at first. If your white count drops too low, your dose gets cut-or stopped. Some patients never get back to the full dose. That’s okay. The goal isn’t maximum drug-it’s enough to prevent rejection without making you sick.

Interestingly, recent studies suggest that how much mycophenolate you’re exposed to over time (measured as AUC, not just blood levels) might predict long-term graft survival better than anything else. That’s why some centers now use AUC monitoring instead of just checking trough levels. It’s more accurate, but it’s also more expensive and not widely available yet.

Steroids: The Double-Edged Sword

Steroids-usually methylprednisolone or prednisone-are the oldest tool in the box. Right after surgery, you get a 1000-mg IV dose. Then, you start oral pills. The plan? Cut the dose fast. By week 3 or 4, you’re down to 15 mg a day. By 2-3 months, you’re at 10 mg. Some people stay on that forever. Others get weaned off entirely.

Why bother with steroids at all? Because they’re cheap, fast-acting, and reduce early rejection better than any other single drug. But the side effects are brutal. Weight gain, especially around the face and belly. Acne. Mood swings. Trouble sleeping. Thin skin that bruises easily. Bone loss. Cataracts. And yes-more diabetes risk on top of tacrolimus.

That’s why steroid-free protocols exist. In a 2005 study, patients given daclizumab (an induction drug) plus tacrolimus and mycophenolate had the same rejection rates as those on steroids. And 89% of them stayed steroid-free after six months. They reported better energy, less weight gain, and fewer skin problems.

So why don’t all centers go steroid-free? Because induction drugs like daclizumab are expensive. And not everyone qualifies. If you’re older, have high antibody levels, or got a kidney from a deceased donor, steroids still give you extra protection. It’s a risk-benefit call, made case by case.

What Goes Wrong? Common Problems and How They’re Handled

Even with perfect adherence, things can go sideways. The biggest threats aren’t rejection-they’re infections and drug interactions.

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is the most common. It’s a virus most people carry quietly. But after transplant, your immune system is too weak to keep it in check. You’ll get tested regularly. If CMV shows up, you’ll take valganciclovir for weeks or months. It’s not fun, but it’s life-saving.

Drug interactions are sneaky. Antifungals like ketoconazole can spike tacrolimus levels. Antibiotics like erythromycin? Same thing. Even St. John’s Wort-common for low mood-can drop tacrolimus to dangerous lows. Always tell your transplant team before starting anything new, even herbal teas.

And then there’s the long game: chronic injury. Even if you avoid rejection for five years, your kidney can still slowly scar. That’s called chronic allograft nephropathy. No drug stops it completely. It’s why 25% of adult transplant recipients end up back on dialysis within five years. It’s not failure. It’s biology. And it’s why researchers are now looking at biomarkers and genetic tests to predict who’s at risk.

What’s Next? The Future of Immunosuppression

Doctors aren’t standing still. The goal now isn’t just to prevent rejection-it’s to do it with fewer side effects. Steroid minimization is already mainstream. Some centers start patients on steroids but drop them by month 3. Others skip them entirely if the patient is low-risk.

Therapeutic drug monitoring is getting smarter. Instead of just checking your blood level at one point in time (trough), they’re measuring how much drug your body is exposed to over 12 hours (AUC). This gives a clearer picture of whether you’re getting enough. It’s not everywhere yet, but it’s coming.

And then there’s pharmacogenomics. Some people have gene variants that make them process tacrolimus slower. Others clear it too fast. Testing for these variants before transplant could mean getting the right dose from day one. No more guessing. No more dangerous spikes or drops.

By 2030, experts predict 15-20% fewer people will be on the classic triple combo. They’ll be on personalized regimens-maybe tacrolimus + sirolimus, or even cell-based therapies. But for now, the trio of tacrolimus, mycophenolate, and steroids remains the most proven, most used, and most effective shield your new kidney has.

Living With the Regimen: Real-Life Tips

Here’s what actually works for people on this combo:

- Use a pill organizer with alarms. Missing a dose-even once-can trigger rejection.

- Take tacrolimus and mycophenolate at least 2-4 hours apart. That helps with stomach upset.

- Keep a log of side effects: diarrhea, tremors, mood changes. Bring it to every appointment.

- Don’t skip blood tests. They’re not optional. They’re your early warning system.

- Wear a medical alert bracelet. It says you’re immunosuppressed. That matters in an emergency.

- Get flu shots, pneumonia shots, and COVID boosters. Avoid live vaccines (like yellow fever).

- Ask your pharmacist to review every new medication. Even aspirin can interfere.

It’s not easy. But it’s doable. Thousands of people live full lives with this regimen. They work. They travel. They raise kids. They go hiking. The drugs are heavy, but they’re not a prison sentence. They’re a tool. And with the right care, they give you your life back.

Can I stop taking my immunosuppressants if my kidney is working fine?

No. Stopping immunosuppressants-even if your kidney feels fine-will almost always lead to acute rejection within days or weeks. Your body remembers the transplant as foreign. There is no safe way to stop these drugs without medical supervision and a very specific plan, usually only tried in research settings after years of stable function.

Why do I need blood tests so often after transplant?

Because the drugs you’re taking have a very narrow range between working and causing harm. Too little tacrolimus? Rejection. Too much? Kidney damage or toxicity. Mycophenolate levels affect infection risk. Blood tests tell your team if your dose needs adjusting. In the first few months, your body is changing fast-your metabolism, your weight, your other medications. Frequent testing catches problems before they become emergencies.

Is it safe to take herbal supplements or vitamins with my transplant drugs?

Most are not. St. John’s Wort can drop tacrolimus levels dangerously low. Garlic, green tea, and echinacea can interfere with how your liver processes drugs. Even high-dose vitamin C or fish oil can affect blood clotting and interact with other meds. Always check with your transplant team before taking anything-not your pharmacist, not your GP. Your transplant center is the only one who knows how your specific combo reacts.

Why do some people get off steroids while others stay on them?

It depends on your risk level. If you’re younger, got a kidney from a living donor, have low antibodies, and no history of rejection, you’re a good candidate for steroid withdrawal. If you’re older, got a kidney from a deceased donor, or had early rejection, steroids are kept longer. It’s not about preference-it’s about matching the level of immune suppression to your personal risk of rejection.

What happens if I miss a dose of my transplant meds?

If you miss one dose, take it as soon as you remember-if it’s within a few hours. Don’t double up. If you miss two doses or more, call your transplant team immediately. Missing doses increases rejection risk. Even one missed dose can cause a spike in immune activity. Some patients have lost their grafts after just a few skipped pills. Consistency isn’t just important-it’s life-saving.

What to Watch For: When to Call Your Transplant Team

You don’t need to panic over every little symptom. But some signs mean trouble:

- Fever over 38°C (100.4°F) that lasts more than 24 hours

- Unexplained swelling in your legs or face

- Sudden decrease in urine output

- Severe diarrhea or vomiting that won’t stop

- Confusion, tremors, or seizures

- Dark urine or yellowing skin (signs of liver issues)

If any of these happen, don’t wait. Call your transplant center. They’ve seen it before. They know what to do. And they’ll want to act fast.

Manan Pandya

December 30, 2025 AT 12:31Tacrolimus levels are such a balancing act-I’ve seen patients crash their grafts by skipping a dose because they "felt fine." The 5-10 ng/mL range isn’t arbitrary; it’s the razor’s edge between survival and rejection. Blood tests aren’t a hassle-they’re your lifeline.

Paige Shipe

December 31, 2025 AT 06:00The idea that you can just stop these drugs if your kidney is "working fine" is dangerously naive. This isn’t a vitamin regimen. It’s a lifelong chemical leash. If you’re not compliant, you’re not just risking your own life-you’re wasting a scarce organ and burdening the system.

Tamar Dunlop

January 1, 2026 AT 22:54Reading this brought me to tears-not from fear, but from awe. The sheer precision of modern medicine, the quiet heroism of patients who take these pills every day, the science that turns a dying body into one that walks, laughs, and hugs grandchildren… it’s nothing short of miraculous. Thank you for writing this with such dignity and clarity.

David Chase

January 2, 2026 AT 02:48MYCOPHENOLATE IS A GUT-KILLER!!! 😩😭 I was on 1g BID and lost 15 lbs in 3 weeks from diarrhea. My doc switched me to Myfortic and I still puke sometimes. And don’t even get me started on steroids-face moon, belly fat, mood swings like a toddler with a sugar rush. 🤢💊 This isn’t treatment-it’s a prison sentence with a kidney attached.

Emma Duquemin

January 3, 2026 AT 03:38Y’all need to hear this: the real MVP isn’t tacrolimus or steroids-it’s the pill organizer with alarms. I used to forget doses until I got one with colored compartments and a voice that yells "MEDS TIME!" in my husband’s voice. Now I’ve been graft-positive for 7 years. Consistency isn’t sexy-but it’s the only thing that keeps you alive. Also-get that medical alert bracelet. I had a fall last year and the ER team didn’t know I was immunosuppressed until they saw the bracelet. Saved my life.

And yes, grapefruit juice is a silent killer. I thought it was just a "health food." Nope. My tac level spiked to 28. I ended up in the hospital. Now I drink orange juice. And I tell every transplant newbie: don’t trust your instincts. Trust your lab results.

Also-St. John’s Wort? Don’t. Even if you think it’s "natural." Your liver doesn’t care. It just sees a chemical warzone. Same with green tea extract. I lost my aunt to rejection because she took "immune-boosting" supplements. Natural ≠ safe. Always. Ask your transplant team. Not Google. Not your yoga instructor.

And for the love of all that’s holy-don’t skip blood tests. I missed one because I was "too busy." Two weeks later, my creatinine was up. Rejection. We caught it early, but it cost me 10% of my kidney function. Don’t be me.

You’re not broken. You’re rebuilt. And this regimen? It’s not a cage. It’s the wings that let you fly again.

Kevin Lopez

January 4, 2026 AT 09:48Tacrolimus AUC > trough. Mycophenolate dose reduction = higher rejection risk. Steroid withdrawal = viable only in low-risk cohorts. CMV prophylaxis mandatory. Pharmacogenomics not yet standard of care. Adherence non-negotiable.

Duncan Careless

January 4, 2026 AT 19:10I’ve been on this combo for 12 years. My kidney’s still ticking. I don’t talk about it much. But I’ll say this: the hardest part isn’t the pills or the blood tests. It’s the loneliness. No one gets it unless they’ve lived it. So thank you for writing this. It’s the first time I’ve felt seen in a long time.

Samar Khan

January 6, 2026 AT 09:42Ugh. Steroids are the REAL villain here. 😒 Why do we still use them? It’s 2025. We have better options. This is medical malpractice disguised as protocol. And don’t even get me started on how they make you look like a balloon animal. 🎈🤢