When your body’s hormone levels go off track for no clear reason - missed periods, low libido, unexplained milk production, or fatigue that won’t quit - the culprit might be hiding in a tiny gland at the base of your brain. Pituitary adenomas, especially prolactinomas, are more common than most people realize. About 1 in 10 people have one of these benign tumors, and while many never know it, others face life-changing hormone disruptions. Prolactinomas alone make up 40 to 60% of all pituitary tumors, and they don’t just cause odd symptoms - they can mess with fertility, bone health, and even your sense of well-being.

What Exactly Is a Prolactinoma?

A prolactinoma is a non-cancerous tumor in the pituitary gland that overproduces prolactin, the hormone responsible for breast milk production. In women, high prolactin levels can shut down ovulation, leading to missed periods (amenorrhea) or infertility. About 95% of women with prolactinomas experience these issues. In men, the effects are subtler but just as real: low testosterone, reduced sex drive, erectile dysfunction, and sometimes breast enlargement. Both genders may feel tired, moody, or notice a drop in muscle mass.

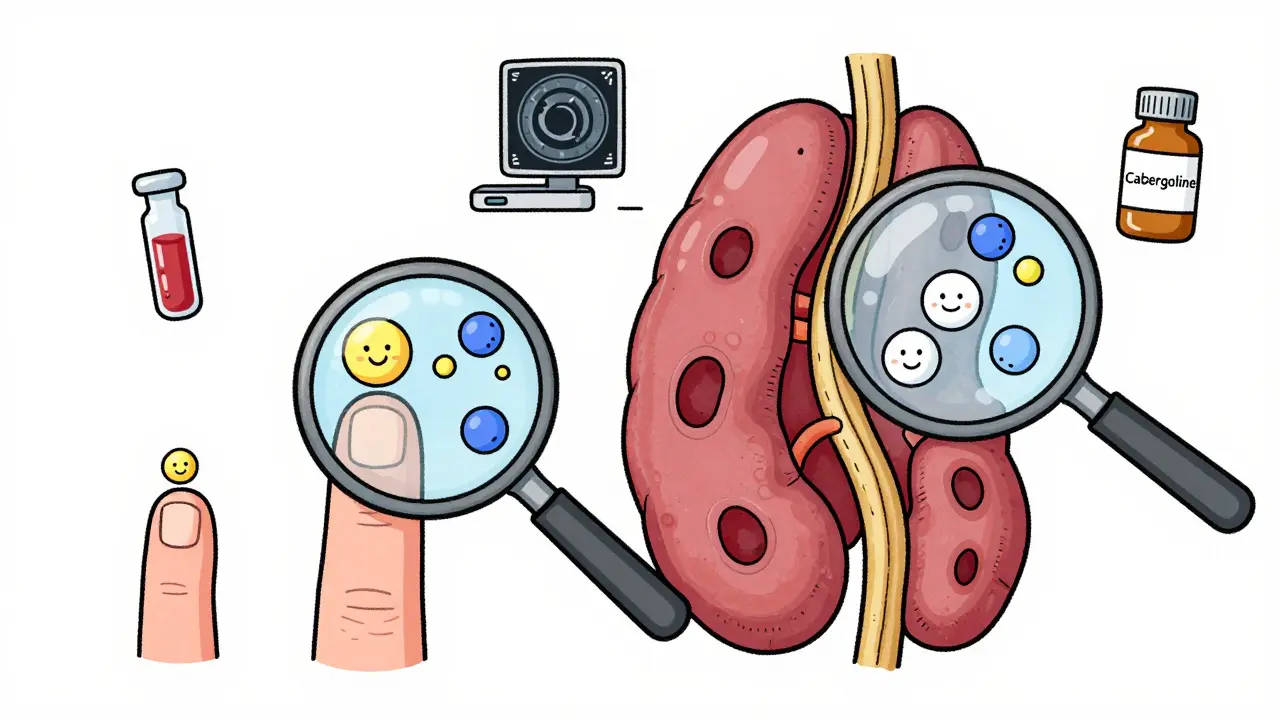

What makes prolactinomas tricky is that they often look like other problems - stress, depression, or even menopause. That’s why many go undiagnosed for years. The average time from symptom onset to diagnosis is nearly two years. A simple blood test can catch it: prolactin levels over 150 ng/mL are 95% specific to prolactinoma. Levels above 200 ng/mL usually mean the tumor is larger than 1 cm (a macroadenoma). Levels below 100 ng/mL are more likely a smaller tumor (microadenoma).

Size Matters: Micro vs. Macro

Pituitary adenomas are classified by size. Microadenomas are under 1 cm - small enough to fit on the tip of your pinky. They rarely press on nearby nerves, so vision problems are rare. Macroadenomas are over 1 cm and can grow upward, squishing the optic nerve. This leads to tunnel vision or blind spots in your peripheral sight. If you’re having trouble seeing the edges of your vision, especially when driving, that’s a red flag.

Here’s the catch: most prolactinomas are microadenomas. About 80% of all pituitary tumors fall into this category. But macroadenomas are more likely to cause noticeable symptoms beyond hormone imbalance. They can also invade nearby structures like the cavernous sinus, making them harder to treat surgically.

How It’s Diagnosed

Diagnosis starts with a blood test. If prolactin is sky-high, doctors rule out other causes - like pregnancy, thyroid issues, or certain medications (antidepressants, antipsychotics, even some heartburn drugs can raise prolactin). If those are ruled out, an MRI is the next step. A high-resolution pituitary MRI with 3mm slices is the gold standard. It shows the exact size, shape, and location of the tumor.

If the tumor is larger than 1 cm, an eye exam for visual field defects is mandatory. You might not notice your vision changing until it’s advanced. A simple test where you cover one eye and stare at a dot while identifying flashing lights can catch early damage.

First-Line Treatment: Dopamine Agonists

For prolactinomas, medication is almost always the first choice. Dopamine agonists like cabergoline and bromocriptine mimic dopamine, the brain’s natural brake on prolactin. They shrink tumors and normalize hormone levels in most cases.

Cabergoline is the clear winner. It works better, lasts longer, and causes fewer side effects. Studies show it normalizes prolactin in 80-90% of microadenomas and 70% of macroadenomas within 3 months. Tumor shrinkage happens in 85% of cases. Most people start with 0.25 mg twice a week. If prolactin doesn’t drop after 4-6 weeks, the dose is slowly increased. Many end up on 0.5 to 1 mg twice weekly.

Bromocriptine works too, but it’s older, requires daily dosing, and causes nausea, dizziness, or lightheadedness in up to 40% of users. A survey of over 1,200 patients found 32% quit bromocriptine because of side effects - only 18% stopped cabergoline.

The best part? You don’t need to take it forever. Some people can stop after 2-3 years if the tumor has fully shrunk and prolactin stays normal. But for others - especially those with larger tumors - lifelong treatment is needed. Missing even one dose can cause prolactin to spike back up within 72 hours.

Surgery: When Medication Isn’t Enough

Not everyone responds to pills. Some can’t tolerate the side effects. Others have tumors so large they’re pressing on the optic nerve - and waiting for medication to work isn’t safe.

Surgery is done through the nose (transsphenoidal), using an endoscope. It’s minimally invasive. Most people go home in 3-5 days. Success rates are high for microadenomas - 85-90% of these are fully removed. But for macroadenomas? Only 50-60% are completely removed. If the tumor has spread into the cavernous sinus (a complex area near major blood vessels), even the best surgeons can’t get it all.

Post-surgery risks include CSF leaks (2-5%), temporary diabetes insipidus (5-10%), and, rarely, pituitary apoplexy (1-2%). About 27% of patients on patient forums reported needing desmopressin for a few weeks after surgery to manage urine output. But 82% said they were satisfied with the results - no scars, quick recovery.

Radiation: The Slow Option

Radiation is usually a last resort. It takes years to work. You might still have symptoms for 1-2 years after treatment. But it’s useful when tumors come back after surgery or don’t respond to meds.

Gamma Knife radiosurgery delivers one precise, high-dose beam. It controls tumor growth in 95% of cases at 5 years and causes less damage to the optic nerve than older radiation methods. But it’s not fast. Only 50-60% of patients see prolactin levels drop to normal within 5 years. And 30-50% end up with hypopituitarism - meaning the pituitary stops making other hormones like cortisol or thyroid hormone. That means lifelong replacement therapy.

Long-Term Risks and Monitoring

Cabergoline is safe for most, but long-term use (over 3 years) at high doses (more than 2.5 mg/week) carries a small risk of heart valve issues. The European Society of Endocrinology recommends an echocardiogram after one year of high-dose treatment and every two years after that.

Even after successful treatment, you need lifelong monitoring. Prolactin levels should be checked every 3 months for the first year, then yearly if stable. MRI scans every 1-2 years catch regrowth early. And if you’re off medication, watch for symptoms. Prolactin can creep back up without warning.

What’s New in 2026

Research is moving fast. In 2023, the FDA approved paltusotine - a new drug originally for acromegaly - and early trials show promise for prolactinomas. Molecular testing is now used to look for mutations like GNAS or USP8, which help predict if a tumor will be aggressive or respond well to drugs.

One of the most exciting developments? AI-assisted surgical planning. Surgeons can now simulate tumor removal before cutting, improving precision. And future treatments might include dopamine-eluting stents placed during surgery or gene therapies targeting inherited mutations like MEN1.

But here’s the reality: 30% of macroadenomas still don’t respond well to current treatments. That’s why ongoing research matters. The goal isn’t just to shrink tumors - it’s to restore normal hormone function without lifelong side effects.

What You Need to Remember

- Prolactinomas are common, treatable, and often missed.

- High prolactin + missed periods or low libido = get tested.

- Cabergoline is the best first-line treatment - better than bromocriptine in every way.

- Size determines your options: small tumors respond great to pills; large ones may need surgery.

- Don’t stop medication without your doctor’s guidance - rebound is fast and dangerous.

- Long-term monitoring isn’t optional. Hormone levels and tumor size change over time.

If you’ve been told your symptoms are "just stress," ask for a prolactin test. It’s cheap, non-invasive, and could change everything.

Can prolactinomas turn cancerous?

No. Pituitary adenomas, including prolactinomas, are almost always benign. They don’t spread to other organs like cancer. But even though they’re not cancerous, large tumors can cause serious problems by pressing on nerves or disrupting hormone balance. That’s why they still need treatment.

Can I get pregnant if I have a prolactinoma?

Yes - but only after prolactin levels are normalized. High prolactin blocks ovulation. Once cabergoline brings levels down, fertility usually returns within a few months. Many women conceive successfully while on medication. Doctors often reduce or stop the drug during pregnancy, since the tumor rarely grows during this time. Regular monitoring is still needed.

Why is cabergoline taken twice a week instead of daily?

Cabergoline has a very long half-life - it stays active in your body for days. Taking it twice a week keeps prolactin levels steady without the spikes and crashes you get with daily pills. It also reduces side effects like nausea. This makes adherence easier, which is key - missing doses leads to rebound.

Do I need to avoid certain foods or supplements?

No special diet is required. But avoid supplements with high doses of vitamin B6 or herbal remedies like chasteberry (vitex), as they can affect prolactin levels and interfere with treatment. Always tell your doctor what you’re taking - even natural products.

What happens if I stop taking cabergoline?

Prolactin levels typically rebound within 72 hours. Symptoms like fatigue, low libido, or irregular periods return. In some cases, the tumor begins growing again. Stopping without medical supervision can undo months or years of progress. Never stop on your own - talk to your endocrinologist first.

Is radiation therapy dangerous for the brain?

Modern radiation like Gamma Knife is highly targeted. It spares healthy brain tissue far better than older methods. The biggest risk isn’t brain damage - it’s hypopituitarism (loss of other hormone production), which happens in 30-50% of patients within 10 years. That means lifelong hormone replacement. Vision damage is rare with Gamma Knife (1-2%) compared to older radiation (5-10%).

Can men develop prolactinomas too?

Absolutely. About 25-30% of prolactinoma patients are men. Symptoms are different: low testosterone, erectile dysfunction, reduced body hair, and sometimes breast tenderness. Men often have larger tumors at diagnosis because symptoms are less obvious, so they’re diagnosed later. That’s why awareness matters - this isn’t just a women’s health issue.

Ariel Edmisten

February 7, 2026 AT 21:58Just got my prolactin levels checked last month after months of fatigue and low libido. Turned out I had a microadenoma. Cabergoline changed everything. No more brain fog. Sex drive back to normal. Honestly, if you’re tired and it’s not sleep or stress, ask for the test. It’s that simple.

Thanks for the post.

Sarah B

February 8, 2026 AT 15:31Heather Burrows

February 10, 2026 AT 09:04It’s ironic isn’t it? We live in a world where we’re told to trust our bodies but then dismissed when we say something feels off. The medical system is built to ignore subtlety until it becomes a crisis. And yet here we are - a tiny gland in the brain holds more power over our lives than we ever realized. We’re not broken. We’re just misunderstood.

But honestly? I’m tired of being told to ‘get tested’ like it’s a solution. What about the people who can’t afford MRI’s? Or the ones whose doctors don’t believe them? It’s not just about knowledge. It’s about access.

Savannah Edwards

February 11, 2026 AT 14:08I’m an endocrinology nurse in Chicago and I see this every single week. Women come in with years of missed periods, depression, weight gain - all written off as stress or PCOS. Men show up with low energy and erectile dysfunction and are told to ‘just lift more’ or ‘take testosterone’. No one thinks to check prolactin.

One guy I remember - 42, engineer, quiet guy - came in because his wife made him. He had a macroadenoma pressing on his optic nerve. He’d lost 30% of his peripheral vision and didn’t even know. That’s how sneaky this is.

Cabergoline works. It really does. But we need more awareness. Especially in primary care. Not everyone has access to an endocrinologist. We need protocols. We need training. And we need to stop making patients feel like they’re overreacting.

Gouris Patnaik

February 11, 2026 AT 18:51Western medicine is so obsessed with pills and scans it forgets the soul. Prolactin is not just a hormone - it’s a mirror of our inner imbalance. Why do so many women with this condition also feel emotionally numb? Is it just chemistry? Or is the body screaming for stillness? We treat the tumor but never ask why it grew.

And yet - no one speaks of this. Just dosage charts and MRI results. We’ve turned healing into a spreadsheet.

Lakisha Sarbah

February 13, 2026 AT 12:30Amit Jain

February 14, 2026 AT 01:11Eric Knobelspiesse

February 15, 2026 AT 19:09So I read this whole thing and I’m just sitting here wondering - if 1 in 10 people have these, why aren’t we screening everyone? Like… why wait for symptoms? Why not just do a routine prolactin test during annuals? It’s cheaper than a cholesterol panel.

Also - typo in the post: ‘2.5 mg/wk’ not ‘2.5 mg/week’ - minor but still… 😅

And side note: bromocriptine is still used in developing countries because it’s cheaper. So maybe the ‘best’ drug isn’t always accessible. Just saying.

Mayank Dobhal

February 15, 2026 AT 22:15Jesse Lord

February 17, 2026 AT 02:09Thank you for writing this. I’ve been sharing this with my patients. Especially the part about vision changes. So many people don’t realize their peripheral vision is fading until it’s too late.

Also - I love that you mentioned the 72-hour rebound. That’s the thing no one talks about. Patients stop meds because they feel fine. Then boom - symptoms come back hard. It’s not ‘in their head’. It’s biology.

Keep spreading awareness. This is the kind of info that saves lives.

AMIT JINDAL

February 18, 2026 AT 18:00Wow. So we’ve got AI surgical planning now? And gene therapies? And dopamine-eluting stents? 😏

Meanwhile in India, 80% of patients still can’t afford a single dose of cabergoline. And here you are, talking about echocardiograms like it’s a spa day. This is why Western medicine is so disconnected. You don’t need a 3mm MRI slice when you don’t have running water.

Maybe instead of ‘exciting developments’, we should be talking about making dopamine agonists affordable globally? Just a thought. 🤔

Catherine Wybourne

February 19, 2026 AT 21:21So… here’s the thing. The post says ‘30% of macroadenomas don’t respond well to current treatments’. And yet - we’re all focused on the 70% who do.

What about the others? The ones who get radiation and then need lifelong hormone replacements? The ones who lose their adrenal function and live on cortisol pills? The ones who still can’t get pregnant even after tumor shrinkage?

There’s a whole hidden population here. The ones who survive… but never feel whole.

Maybe the real breakthrough isn’t in the drug… but in how we care for people after the cure.