Walkability Score Calculator for Low-Density Areas

Estimate walkability scores for low-density areas using factors from the article: block length, density, mixed-use development, micro-transit access, and infrastructure features.

Quick Takeaways

- Low density can improve street calmness, making sidewalks and bike lanes feel safer.

- Design tricks-like mixed‑use blocks and shorter street networks-counteract the spread‑out nature of low‑density areas.

- Policy tools such as flexible zoning and transit‑oriented planning turn low‑density suburbs into active, health‑promoting neighborhoods.

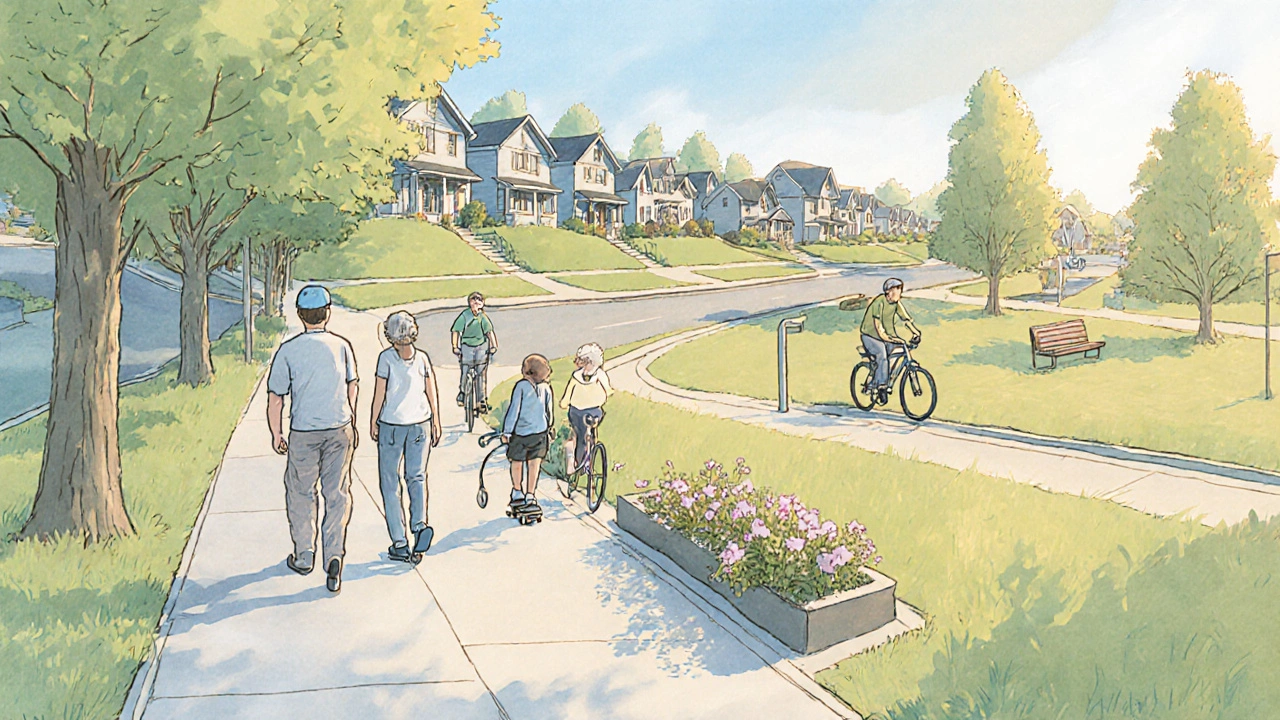

When people talk about making a place walkable or bike‑friendly, the first thing that pops up is usually low density is a development pattern where housing, jobs, and services are spread over a larger land area, resulting in fewer units per hectare. It sounds like the opposite of walkability, right? Fewer destinations close by mean longer trips, and longer trips often mean people drive. But the reality is more nuanced. With the right design moves, low‑density neighborhoods can still feel safe for pedestrians and cyclists, encourage active travel, and boost public health.

Let’s unpack how low density interacts with the three big pillars of an active community: walkability is a measure of how easy and pleasant it is to move around a place on foot, bike‑friendliness is a assessment of how well a street network supports safe and convenient cycling, and health outcomes are the physical and mental effects of the built environment on residents. By weaving together thoughtful design, flexible policy, and community engagement, planners can turn low‑density sprawl into a place where you actually want to walk or bike.

Why Low Density Isn’t a Deal‑Breaker for Active Travel

Low density often gets a bad rap because it can increase distances between homes, shops, schools, and transit stops. However, three factors can soften that impact:

- Street network design: A fine‑grained grid or a series of short, interconnected cul‑de‑sacs reduces the length of any single route, making walking and cycling feel less daunting.

- Mixed‑use development: By clustering apartments, offices, grocery stores, and parks within a few blocks, you create pockets of activity that break up the spread‑out pattern.

- Transit‑oriented planning: Placing frequent bus or tram services at the heart of low‑density zones brings an anchor point that people can walk or bike to.

These three levers are the backbone of complete streets is a design approach that accommodates pedestrians, cyclists, transit users, and drivers on the same roadway and are especially powerful when the overall density is low.

Design Strategies That Make Low‑Density Areas Walkable

Below are the most effective tactics, illustrated with real‑world examples from the UK and North America.

- Reduced block lengths: In Milton Keynes, planners introduced a network of "grid squares" that are only 400 m on a side. Residents report a 30 % increase in walking trips despite the city's overall low density.

- Pedestrian shortcuts: Adding mid‑block passages through parks or school grounds shortens routes by up to 20 % and creates more direct walking lines.

- Sidewalk widenings and buffers: Wider footpaths with greenery give pedestrians a sense of safety, especially where traffic volume is low but vehicle speed is high.

- Frequent micro‑transit stops: In Surrey, a new on‑demand bus service stops every 300 m, encouraging people to bike or walk the short distance to catch a bus.

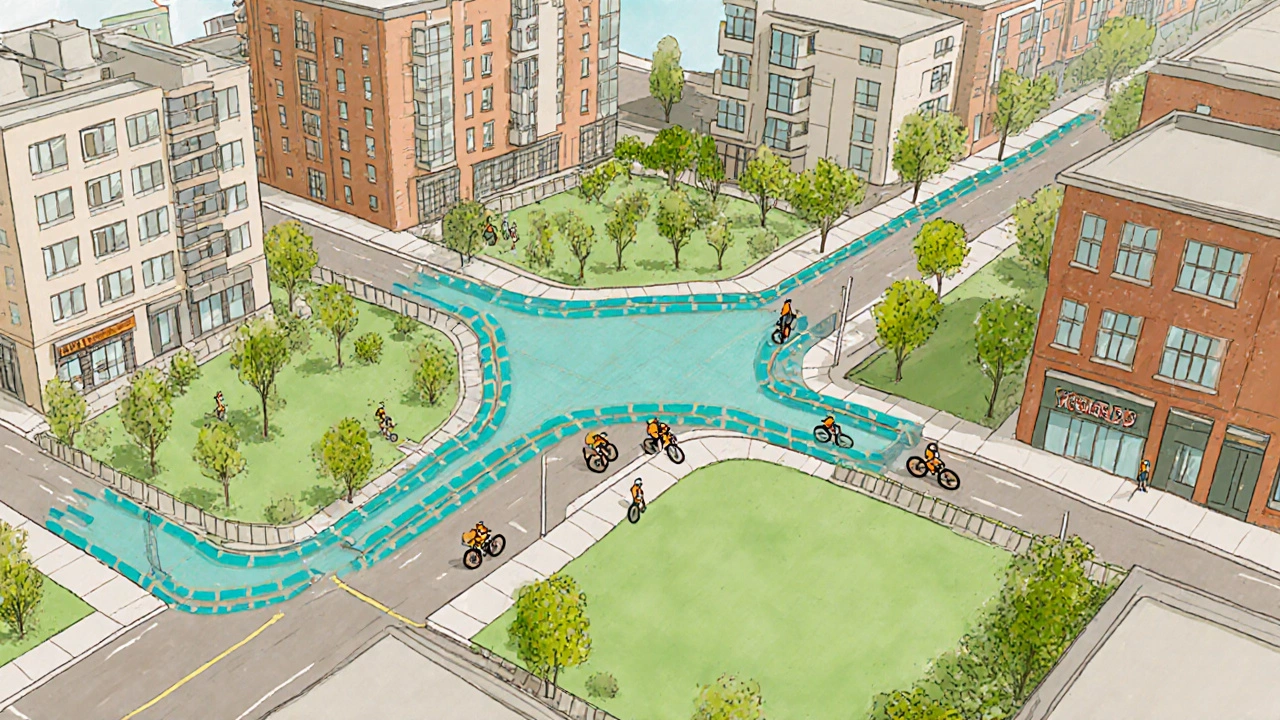

Bike‑Friendly Adjustments for Sprawling Suburbs

Cyclists need continuity. A single bike lane that disappears at a cul‑de‑sac can feel like a dead end. Here’s how low‑density planners keep the flow:

- Protected bike boulevards: Low‑speed streets with physical barriers (planters or curbs) guide cyclists safely through residential blocks.

- Shared‑use paths: Where road space is tight, a separate path alongside a footway gives cyclists a dedicated space while still connecting to the street network.

- Bike‑share hubs: Placing docking stations at community centers or schools creates a “last‑mile” solution without needing every home to have a bike rack.

- Designated bike shortcuts: Similar to pedestrian shortcuts, these cut across large parcels or follow natural corridors (riverbanks, rail trails).

Policy Tools: Zoning, Incentives, and Standards

Design alone isn’t enough. Government policies shape what gets built and how. The following instruments are common in the UK and Europe:

- Form‑based codes: Instead of focusing on land‑use percentages, these codes dictate building placement, street frontage, and public realm standards, encouraging active frontages even in low‑density zones.

- Density bonuses for active‑transport amenities: Offer developers extra floor‑area ratio (FAR) if they include bike storage, wide sidewalks, or pedestrian plazas.

- Transit‑oriented zoning (TODZ): Reduce parking minimums around bus or rail stations, prompting residents to rely on public transport and active modes.

- Design guidelines for “complete streets”: Mandate curb extensions, reduced lane widths, and cross‑walk treatments that calm traffic.

Comparing Density Levels and Their Walkability Scores

| Density | Typical Block Length | Average Walk Score* | Bike Infrastructure Index | Key Design Levers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low (≤10 dwellings/ha) | 400‑600 m | 45‑55 | 30‑45 | Mixed‑use nodes, micro‑transit, short‑cut pathways |

| Medium (10‑30 dwellings/ha) | 250‑400 m | 55‑70 | 45‑60 | Complete streets, bike boulevards, higher FAR |

| High (≥30 dwellings/ha) | ≤250 m | 70‑85 | 60‑80 | Dense grid, extensive transit, minimal parking |

*Walk Score is a composite metric ranging from 0 (car‑dependent) to 100 (walk‑perfect).

Real‑World Success Stories

Portland, Oregon (USA) - The city’s “20‑minute neighborhood” program targets low‑density suburbs with a mix of pocket parks, bike‑share stations, and frequent bus service. Since 2019, walking trips in those zones rose by 22 %.

Walthamstow, London (UK) - By retrofitting a low‑density council estate with a series of pedestrian shortcuts and a protected bike lane that links to the Central Line, the borough saw a 15 % drop in car travel during peak hours.

Melbourne’s “Suburban Rail Loop” (Australia) - The plan deliberately pairs low‑density housing clusters with high‑frequency rail stations, ensuring each cluster remains within a 10‑minute walk.

Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

- Assuming low density equals car dependence: Without active‑transport infrastructure, residents will default to the car. Provide concrete alternatives first.

- Over‑relying on parking minimums: Too many parking spots eat up space that could become sidewalks or bike paths.

- Ignoring community input: Residents may resist new bike lanes if they feel unsafe. Engage early and co‑design solutions.

- Neglecting maintenance: Even the best-designed paths become unusable if not kept clear of debris or overgrown vegetation.

Steps to Transform a Low‑Density Neighborhood

- Map existing destinations (schools, shops, transit stops) and identify gaps of more than 500 m.

- Introduce short‑cut pathways-both pedestrian and cyclist-through underused parcels or green spaces.

- Adopt a form‑based code that mandates a minimum sidewalk width of 2 m and a protected bike lane of 1.5 m on all arterial streets.

- Partner with the local transit agency to place a high‑frequency bus stop within 300 m of the newly created “activity node.”

- Launch a community‑driven “walk‑bike challenge” to encourage residents to try the new routes, collecting data on usage.

Future Outlook: Low Density in 2030 and Beyond

Climate goals, housing shortages, and the push for healthier lifestyles are reshaping how planners treat low density. Emerging trends include:

- “15‑minute suburbs” - A twist on the 15‑minute city, focusing on bringing essential services within a 15‑minute walk or bike ride even in spread‑out districts.

- Smart micro‑mobility hubs - Integrating e‑scooters and shared e‑bikes with local transit to cut down the perceived distance.

- Green corridors - Using linear parks as natural shortcuts that double as biodiversity corridors.

When these strategies align, low density transforms from a barrier into a catalyst for vibrant, health‑promoting communities.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can low‑density neighborhoods ever achieve a Walk Score above 70?

Yes, but it requires a cluster of amenities within walking distance, a fine‑grained street network, and supportive policies like reduced parking minimums. The table above shows that with targeted design, low‑density areas can reach the 55‑70 range, and in exceptional cases-like Portland’s 20‑minute neighborhoods-scores can climb above 70.

What is the most cost‑effective bike‑friendly upgrade for a suburb?

Adding protected bike boulevards on existing low‑traffic streets typically costs far less than building separate bike lanes on major roads. The key is to re‑stripe the road, add low‑curb barriers, and install clear signage.

How does transit‑oriented zoning help low‑density areas?

By allowing higher building heights and reduced parking near a transit stop, TODZ concentrates activity in a small footprint. Residents can walk or bike to the station, cutting the need for a car even when houses are spread out elsewhere.

Are pedestrian shortcuts legal in most UK cities?

Yes, provided they receive planning permission and meet safety standards. Many councils use Section 106 agreements to secure rights‑of‑way for community‑led pathways.

What data should I collect to prove a low‑density design works?

Track counts of pedestrians and cyclists on key routes, survey resident travel habits pre‑ and post‑intervention, and monitor health indicators such as active‑travel minutes per week. Comparing these metrics against baseline car‑trip data provides a clear picture of impact.

Tammy Sinz

October 22, 2025 AT 18:37When you dissect low‑density paradigms through the lens of multimodal connectivity, the jargon‑heavy discourse reveals opportunities for tactical street retrofits. The framework mandates integrated sidewalks, protected bike boulevards, and micro‑transit nodes to mitigate sprawl inertia. Planners must leverage form‑based codes to dictate frontage continuity, ensuring active transport amenities are not afterthoughts. Moreover, density bonuses should be conditioned on tangible pedestrian and cycling infrastructure deliverables. This synergistic approach aligns with climate resilience metrics while preserving the spatial benefits cherished by suburban constituents.

Rachael Turner

October 29, 2025 AT 16:17Low density can feel like a barrier but also a canvas for creative pathways the street grid can be re‑imagined through subtle cuts and shared spaces it invites a slower rhythm of movement that nurtures community ties and encourages reflection

Suryadevan Vasu

November 5, 2025 AT 14:57From a planning perspective, compressing block lengths and adding buffered sidewalks are precise interventions that directly lower perceived travel distances. The data shows measurable increases in pedestrian counts when such measures are implemented.

Don Goodman-Wilson

November 12, 2025 AT 13:37Oh sure, let’s just sprinkle bike lanes in the middle of nowhere and expect everyone to ditch their cars. Because nothing says “walkable” like a lone bike lane that ends at a cul‑de‑sac, right? Sarcasm aside, low‑density areas need far more than token infrastructure to become truly active.

Bret Toadabush

November 19, 2025 AT 12:17They don’t want you to know that the real plan is to keep us dependent on cars. The whole “micro‑transit” buzz is just a distraction – it’s all part of the big agenda to control movement and waste our resources.

Iris Joy

November 26, 2025 AT 10:57Let’s break down the process step by step so it feels doable and not overwhelming. First, map out every existing amenity – schools, grocery stores, parks, transit stops – and note any gaps that exceed 500 meters. Next, identify underused parcels or green corridors that could host mid‑block shortcuts; these are low‑cost interventions that instantly cut travel distance. Then, work with your local council to adopt a form‑based code that mandates a minimum sidewalk width of two meters and a protected bike lane of at least 1.5 meters on all arterial streets. Secure funding for curb extensions and traffic‑calming measures, such as raised crosswalks, which further encourage pedestrians to feel safe. Partner with the transit agency to place a high‑frequency bus stop within three hundred meters of each new activity node – this creates a reliable anchor point for both walkers and cyclists. Promote community involvement by launching a “walk‑bike challenge” that rewards residents for using the new routes, and collect data on usage to refine the design over time. Maintain the infrastructure regularly: clear debris, trim vegetation, and repair pavement cracks to keep the paths inviting. Celebrate small wins publicly, like a new shortcut opening, to build momentum and reinforce the health benefits of active travel. Finally, track health indicators such as average active‑travel minutes per week and compare them to baseline car‑trip data; this evidence will support future investments and prove the model’s success. By following these steps, you transform a low‑density suburb from a car‑centric landscape into a vibrant, health‑promoting community that residents actually enjoy.

Sarah Riley

December 3, 2025 AT 09:37Implementing protected bike boulevards yields a cost‑effective modal shift catalyst.

Christa Wilson

December 10, 2025 AT 08:17Love seeing these ideas come together – it’s exactly the kind of positive change we need! 🌟🚶♀️🚲

John Connolly

December 17, 2025 AT 06:57Great overview! As someone who works on community outreach, I can vouch for the power of clear, actionable steps. Let’s keep the momentum going and get those micro‑transit hubs up and running. The more we collaborate, the faster we’ll see real, measurable improvements in walkability and bike‑friendliness.

Tim Blümel

December 24, 2025 AT 05:37Curious about the data collection methods you recommend – do you prioritize automated counters, resident surveys, or a mix? 🤔📊 Both quantitative counts and qualitative feedback give a fuller picture, and using open‑source tools can keep costs low while ensuring community buy‑in.

Joanne Ponnappa

December 31, 2025 AT 04:17It’s wonderful to see such thoughtful planning. Simple steps like widening sidewalks can make a big difference for everyday walkers. 😊👍

Michael Vandiver

January 7, 2026 AT 02:57Loving the vibe here – let’s keep the ideas flowing! More bike lanes, more greenspaces, more community love 🌱🚴♂️💬

Emily Collins

January 14, 2026 AT 01:37While the technical details are impressive, the human element often gets lost – we need to remember that every path we build will be walked by families, seniors, and kids, each with their own stories and hopes.