If you have recent African ancestry, you might carry a genetic variant that increases your risk of kidney disease - not because of lifestyle, not because of age, but because of something written in your DNA long before you were born. This isn’t rare. About 1 in 8 African Americans carries two copies of these variants, putting them at significantly higher risk. And yet, most people - even many doctors - have never heard of it.

What Is APOL1, and Why Does It Matter?

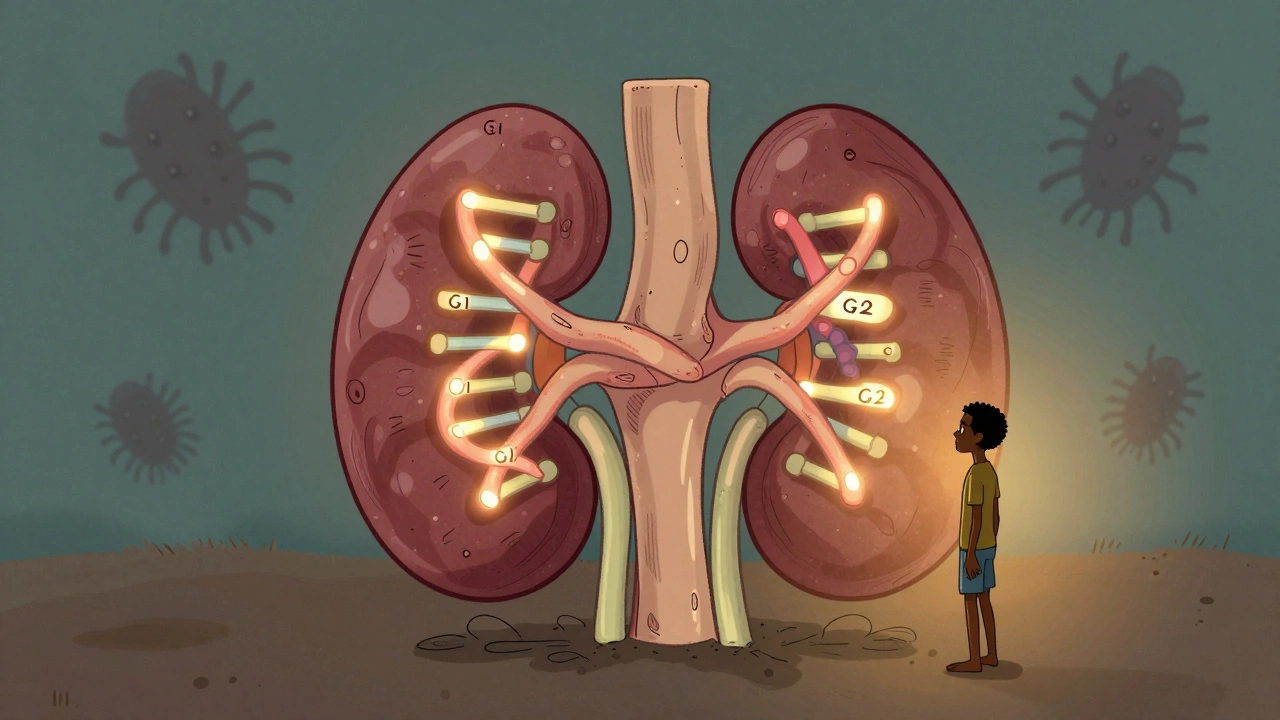

The APOL1 gene makes a protein that helps your body fight off certain parasites. In parts of West Africa, where deadly sleeping sickness is common, people with specific versions of this gene - called G1 and G2 - were more likely to survive. Over thousands of years, these versions became common in those populations. But here’s the catch: the same versions that protect against parasites can damage your kidneys.

It’s not enough to have just one copy. You need two - either two G1s, two G2s, or one of each. That’s called a high-risk genotype. About 13% of African Americans have this combination. Among those who develop non-diabetic kidney disease, nearly half carry these variants. That’s not a coincidence. It’s the reason kidney failure rates are 3 to 4 times higher in people of African descent compared to other groups in the U.S.

What makes APOL1 different from most genetic diseases is that it doesn’t guarantee illness. Most people with high-risk genotypes - about 80% - will never develop kidney problems. Something else has to trigger it. That’s called a "second hit." It could be HIV, lupus, obesity, high blood pressure, or even certain viral infections. That’s why some people live to 80 with no issues, while others start losing kidney function in their 30s.

Which Kidney Diseases Are Linked to APOL1?

APOL1 doesn’t cause one single disease. It makes you more vulnerable to specific types of kidney damage:

- Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) - a condition where parts of the kidney’s filtering units scar over. It’s one of the most common causes of kidney failure in young adults with APOL1 risk variants.

- Collapsing glomerulopathy - a severe, fast-progressing form often seen in people with HIV. In fact, nearly half of all HIV-related kidney failure in people of African ancestry is tied to APOL1.

- Hypertensive nephrosclerosis - kidney damage from high blood pressure. In people with APOL1 risk, even mild hypertension can cause faster damage than expected.

These aren’t rare conditions. They’re the leading causes of kidney failure in Black communities. And because they’re often mistaken for "just high blood pressure" or "aging," they’re diagnosed late - when treatment options are limited.

Why Race Isn’t the Right Word Here

You’ll hear people say "Black people are at higher risk." That’s misleading. It’s not about race - it’s about ancestry. These variants came from West Africa. Someone with Nigerian, Ghanaian, or Jamaican roots is at risk. Someone with European or East Asian ancestry, even if they identify as Black, isn’t. And someone with African ancestry who grew up in Sweden or Australia still carries the same genetic risk.

Doctors used to adjust kidney function estimates based on race. They assumed Black patients naturally had higher muscle mass, so they gave them a "race correction." But that practice ignored genetics. In 2022, the American Medical Association officially recommended stopping race-based calculations. APOL1 research made it clear: we need to look at genes, not skin color.

Testing for APOL1: Who Should Get It?

Genetic testing for APOL1 has been available since 2016. It’s a simple blood or saliva test. But who should get it?

- Anyone with recent African ancestry who has been diagnosed with kidney disease - especially if it’s not caused by diabetes or high blood pressure.

- People considering becoming a living kidney donor with African ancestry. If they carry two risk variants, donating could put their own kidneys at risk.

- Those with a family history of early kidney failure (before age 60) and African ancestry.

The test costs between $250 and $450 out of pocket. Insurance doesn’t always cover it - yet. But if you’re at risk, it’s worth asking your doctor. Knowing your status changes everything.

What Happens After a Positive Result?

Getting a positive result doesn’t mean you’re doomed. It means you’re in a better position to protect yourself.

Here’s what experts recommend:

- Annual urine test - check for protein (albumin-to-creatinine ratio). Early signs of kidney damage show up here before blood tests change.

- Keep blood pressure under 130/80 - even if you feel fine. Medications like ACE inhibitors or ARBs are often used to protect the kidneys.

- Avoid NSAIDs - drugs like ibuprofen and naproxen can hurt kidneys faster in people with APOL1 risk.

- Manage weight and diabetes - if you have either, controlling them is even more critical.

- Get vaccinated - especially for HIV and hepatitis. Infections can act as "second hits."

One woman, Emani, found out she had high-risk APOL1 during a routine check-up at age 32. Her kidneys were still normal. She started monitoring her urine, cut out processed foods, and began taking blood pressure meds. Five years later, her kidney function is unchanged. She didn’t prevent the risk - she prevented the damage.

The Emotional Weight of Knowing

For many, learning about APOL1 brings relief - finally, an explanation for why they or a loved one got sick. But it also brings anxiety.

One man on a kidney support forum wrote: "My doctor said I have a 1 in 5 chance of failing kidneys. That’s not a number. It’s a shadow I carry every day."

Another, a medical student with the same genotype, checks her blood pressure every week and gets urine tests yearly. "I’m not scared," she says. "I’m prepared."

That’s the difference between fear and empowerment. Knowledge gives you control. Without it, you’re guessing. With it, you’re acting.

What’s Next? New Treatments on the Horizon

For decades, there was nothing doctors could do to stop APOL1 damage. But that’s changing.

Vertex Pharmaceuticals is testing a drug called VX-147 - the first treatment designed to block the harmful effects of APOL1. In a 2023 trial, it cut protein loss in the urine by 37% in just 13 weeks. That’s a big deal. Less protein in urine means slower kidney decline.

The NIH is also running a 10-year study tracking 5,000 people with high-risk APOL1 to figure out what triggers kidney damage and how to stop it. By 2025, we should have better tools to predict who’s most likely to get sick.

And if these treatments work, they could reduce kidney failure rates in African ancestry populations by up to 35% by 2035. But only if they’re accessible. Right now, only 12% of low-income countries can even test for APOL1. That’s a global injustice.

Final Thoughts: Knowledge Is Power

APOL1 isn’t a death sentence. It’s not even a guarantee of disease. It’s a warning light - one that most people never see. But now you know it exists.

If you have African ancestry and have ever had unexplained kidney problems, or if someone in your family lost kidneys young, ask about testing. Don’t wait for symptoms. Don’t let doctors dismiss your concerns as "just hypertension."

This isn’t about blame. It’s about biology. It’s about history. It’s about finally seeing the real cause behind a health gap that’s lasted for generations. And it’s about taking action - before it’s too late.

Michael Feldstein

December 5, 2025 AT 00:19Martyn Stuart

December 6, 2025 AT 19:53Bill Wolfe

December 8, 2025 AT 05:06Jessica Baydowicz

December 8, 2025 AT 08:09Gareth Storer

December 9, 2025 AT 05:39Benjamin Sedler

December 11, 2025 AT 01:50jagdish kumar

December 13, 2025 AT 01:32Pavan Kankala

December 13, 2025 AT 11:42